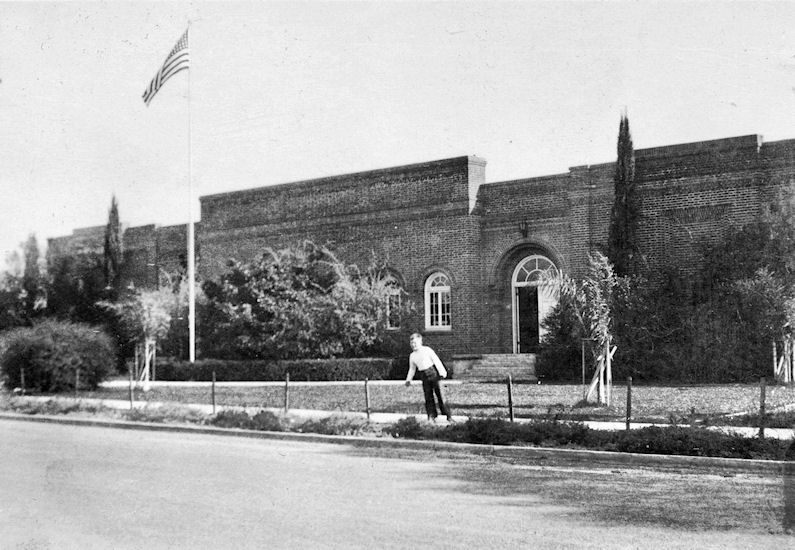

West Orange School, 1890-1904; photo circa 1900 (courtesy Pat Hearle).

The First One Hundred Years of West Orange Elementary, 1890-1990

I have had a soft spot for the history of West Orange School for a good many years now, and so now that its Centennial is upon us, I could not pass up the opportunity to put together at least a brief account of the school’s history. I did not attend West Orange School myself, but I had some dear old friends who did (my mother also worked there as a teacher’s aide).

I also felt some obligation to take an active role in West Orange’s Centennial since I had been responsible for postponing the celebration on two different occasions in the past (the confusion stems from a plaque outside the school which gives its founding date as 1886).

What follows is in no way intended to be the final word on the history of West Orange School. Think of it instead as an outline, an introduction to the first 100 years of what is now the second oldest school in the Orange Unified School District --and also one of its best.

----Phil Brigandi, September, 1990

A Place Called West Orange

What we think of today as the City of Orange includes what were once a number of small outlying farming communities -- places like Olive, El Modena, McPherson, and West Orange.

Actually, West Orange was never really a town, just a few families living out towards the Santa Ana River west of Orange. The area owes its name to the Southern Pacific Railroad’s West Orange depot there.

The SP’s Anaheim Branch was the first railroad built into what is now Orange County. It reached Anaheim early in 1875, and in 1877 was extended into Santa Ana. Orange was not included on the line, but in 1880, after the town had grown up a little more, the company added a depot about three miles out from the center of Orange, which they dubbed “West Orange.” If people needed to use the railroad they would just have to come to it.

The depot was located along Flower Street, a little ways south of LaVeta (the site is now buried under the freeway). It remained in use until 1918. Within a few years after its completion there was regular stage coach service back and forth from downtown Orange, plus a daily mail delivery to the Orange Post Office.

People had begun settling in the West Orange area long before the railroad arrived there, though. Charles Clough, who handled the mail route, bought 10 acres there shortly after 1876. His ranch was located at what is now the corner of Palmyra and Feldner -- it cost him $10 an acre. He cleared the land and planted apricots, oranges, lemons, walnuts and some alfalfa down at the lower end of the ranch for his animals.

Clough’s daughter, Lena Mae Thompson (1891-1983) always had vivid memories of her childhood:

“I was born right here in Orange in ... December, 1891. And I was born in the same bed that my sister was born in, but she was born in Los Angeles County and I was born in Orange County. It had changed between the time we were born.... We didn’t have any money ... none of us had any money. We were all as poor as we could be.... We had very little social life. We knew only our neighbors. It wasn’t easy to get away, to go places. We had two old horses that did the plowing and all the ranch work, and if we went some place [we took them].... The coyotes were awful thick at that time. I remember they had to keep the chickens locked up. If they would let the chickens out in the evening the coyotes would grab ‘em.... Nowadays all the young folks know to eat is a hamburger and some french fried potatoes and a bottle of Coke. Well now, those things were unheard of in our day. We ate beans and potatoes and the vegetables that we grew on the place, and cornbread, and oatmeal mush for breakfast. We never bought anything prepared like you can now. When I think of the millions of kinds of prepared cereals . . . that was unheard of. People ate oatmeal or cornmeal mush. And most of the folks cured their own pork. We always had ham and homemade sausage and bacon. What we would do on the ranch was buy two little pigs in the spring and have them out back of the barn and all the surplus vegetables and things ... we’d throw it in the pigpen ... and all the sour milk. So then, when fall came, the pigs were butchered and made into hams and bacon and sausage ... then the parts they felt they couldn’t eat, that was made into soap. The women made their own laundry soap.... We had no store-bought playthings, we just played with what there was to play with. And the folks, my dad especially, had quite a knack for making things for us. He’d make us little tops out of an empty spool, put a pin through it and we’d spin that ... and we had whistles made out of willow when we’d go over hunting for rabbits [along the Santa Ana River]. He’d cut a willow branch and make a whistle -- I wish I knew how he did it.”

Another early West Orange settler was W. A. Dyer, who came in 1892. Some of his recollections are preserved in a 1938 interview published in the old Orange Daily News:

“W.A. Dyer, of West Palmyra avenue … this year recalls 50 years as a citizen of California, 46 of which have been spent on the spot where he lives today.

“Just recently, surrounded by members of his family, relatives and friends, he celebrated his eightieth birthday. Eighty years young would best describe this pioneer -- small in stature; white hair and mustache; kindly eyes.... Known affectionately as the ‘Mayor’ of West Orange, Dyer saw this community [Orange] rise from a few buildings, a plaza ‘no bigger than a dollar’; from an area of vineyards to one of the richest citrus producing areas in the world.

“Chapman and Main were the only roads in West Orange at the time; more trails than roads – muddy and rough in winter and dusty in summer. Dyer helped to grade the streets for the first time. Santa Ana was but a small town then.... Dyer expects to see a great population every year; a community of small property owners taking the place of large land holdings.

“Orange’s access to outside communication centered in the West Orange depot.... Much of the territory in this section was swamp land, Dyer recalled. At that time it was possible to get water at a depth of 10 feet on his present property. ‘Now you have to go down 150 feet.’

“There were no bridges over the river then. Channels were quite deep. Danger of quicksand was present and crossings therefore hazardous. Early day residents minimized the danger by having sheepherders drive their flocks across and back. The hoofs of the sheep packed the sand and made the crossing for horses and wagons possible.

“The first Chapman avenue bridge, a wooden structure, was built several years after Dyer’s arrival.... Reminiscent of early days are the trees which Dyer planted some 45 years ago on his place, and the old barn which forms a picturesque background to a yard shaded by a huge spreading pepper tree.... He is the father of seven children ... Mrs. Dyer passed away 10 years ago.

“‘Yes, I have seen a great change in the last 50 years,’ Dyer explained, in telling of an area which modern generations will never experience. ‘But,’ he added, ‘I’d like just as much to see what the next 50 years wi1l bring.’”

Dyer’s home still stands today, and is still occupied by his descendants. His only surviving child is his son, Bi11 Dyer, who was born in the old house in 1896. He can remember West Orange when the area was still largely planted to apricots.

“They went to oranges later,” he recalls. “[My dad] had apricots for years and finally switched to oranges and walnuts.” Most of the ‘cots were cut and dried in the sun. The Dyers would hire as many as 60 people to work in their apricot camp, and used 3,000 trays to lay out the fruit (all of which had to be washed by Bill and his brother – “it was quite a job.”)

Life was built around agriculture in West Orange in those days, with each family caring for themselves and their ranch. There was no “downtown” -- no stores, no churches, no post office. All of those things meant a trip into Orange. In fact, besides the depot, West Orange had only one other public building -- the West Orange School.

A School for West Orange

Orange’s first school opened in 1872, just one year after the townsite had been laid out. It was the only school then for children in the area. But as the communities around Orange began to grow, new school districts began forming. Olive was the first in 1876. Villa Park followed in 1881, and El Modena got its own district in 1886. Only West Orange stayed on as a part of the Orange District.

Finally, in 1890, the parents of West Orange decided that they were ready for a school of their own· They petitioned the new Orange County Board of Supervisors to create a separate school district to serve their area. Their goal was to keep their children from having to make that long walk all the way into Orange, and also (apparently) to try and lower their taxes by getting out from under the bonded debt of the Orange School District. Charles Bush led the drive, and his name topped the list of 17 signatures on their petition.

In February, the residents had their hearing before the Board of Supervisors. The taxation issue drew most of the argument. J.P. Greeley, the County Superintendent of Schools, took no position on the question, but the Trustees of the Orange School District were solidly opposed to the proposal. According to the Orange Post:

“After a lengthy discussion pro and con, in which all the advantages and disadvantages of creating the new district were ably set forth, and to which the Board gave a patient hearing, Supervisor Armor [Orange’s representative on the Board] moved that the petition be received and the prayer of the petitioners refused. On this motion the Board voted unanimously in the affirmative, and the Orange School District remains intact.”

Suspiciously soon after that meeting, on April 21, 1890, the Trustees of the Orange School District set off the for West Orange depot to meet up with other interested parties .”.. for the purpose of arranging to select a lot in that locality whereon to build a school house.” Present were Trustees William Blasdale and Jesse Arnold (the third member of the Board, Andrew Cauldwell, was not present) and community leaders D.C. Pixley, Joseph Baxter, James Fullerton and Sam Armor. (Blasdale was then also serving as Mayor of Orange, Cauldwell was our City Clerk, and Arnold was a downtown storekeeper. Pixley was a well-known local businessman, and Fullerton was the editor of the weekly Orange News.)

At the depot they were joined by Charles Bush, Superintendent Greeley and several other West Orange residents. According to Fullerton’s account in the News:

“The first matter considered was the site for the school. The two corners at the junction of the continuation of La Vita [sic] avenue and the road [Flower Street] that runs north and south past the Southern Pacific depot were the choice of the people of the section. Dr. Greenleaf, through Mr. Bush, made offer of an acre on the southeast corner for $300 or 1½ acre for $400. The owners of the other corner were interviewed but declined to sell at a price as low as Dr. Greenleaf had offered. The trustees concluded to accept Dr. Greenleaf’s offer of an acre on condition that it could be a square clear of roads.

“The matter of a school building was then talked over and it was decided that a building somewhat similar to that lately built on the school property at Orange [the new primary building] would answer all requirements....

“The meeting was quite harmonious, and the probabilities are that a school to satisfy the residents of West Orange will be ready for the accommodation of the children at the opening of the fall term. Mr. Bush estimates that seating room will at once be required for about fifty children.

“The matter of a school for this section has been agitated for some time, occasionally with considerable warmth, and it is gratifying to have the question amicably settled.”

To raise the funds needed for the new school, the Trustees then called a special election on May 17th for the residents of West Orange to vote on a $1,000 tax increase. According to Jesse Arnold, “we have asked for $1,000 thinking [that] with the funds on hand, we will be able to build a [school] house costing $800 and furnish [it] with seats and etc.”

The election was decisive – if small. The vote was 12 to 0 in favor of the extra tax burden.

Several other steps were then needed to meet all the legal formalities. At their June 16th meeting the School Board sent out a “Proposal for Bids for West Orange School House Site.” Two offers were received in time for their July 7th meeting: Dr. Greenleaf’s already viewed property, and another parcel nearby in the Shaffer Tract. The final, official vote was to buy one acre from Dr. Greenleaf for $300.

As a further step forward, the Trustees also hired West Orange’s first teacher that day, Miss Luella Bryan. Her salary was set at $70 per month (later lowered to $60).

Next, the Trustees put out a “Proposal for Bids” for the construction of the new school house. C.B. Bradshaw, Orange’s leading architeet (and not coincidentally, Orange County’s only full-time architect then) provided the plans and was also retained to supervise the construction. His fee was $30.

The four bids eventually received were opened on July 28th and ranged from $920 to $745. Albert Meacham’s low bid of $745 was immediately accepted, and for an additional $25 he agreed to add two feet to the building’s dimensions, bringing them to a total of 22 x 34 feet. Before long, he was on the job.

Towards the end of August, James Fullerton went out to West Orange to see how things were coming along. On August 27th he reported in the Orange News:

“We paid a visit yesterday to the new schoolhouse near the Southern Pacific depot, and found the work nearly completed. The carpenters were putting on the finishing touches and the painters had a day’s work to do. The building presented a neat and snug appearance inside and out, and the work seems well done. The wall s inside to a convenient height are covered with blackboard, and the light and ventilation will be excellent. Surveyor Bathgate was engaged in laying off the square acre that comprises the school grounds, and it will be fenced off from the adjoining property at once. Seats have been purchased and all will be in readiness for occupancy at the opening of the forthcoming school term.”

The actual opening day for West Orange School came on Wednesday, September 10, 1890. The enrollment was about 30 students in grades 1-5, all of whom sat together in the same room and were taught by the same teacher. The school served an area that stretched -- in rough terms -- from the Santiago Creek to Chapman Avenue, and from Main Street west to the Santa Ana River. Some of the families that came to live in that area were the Suttons, the Smileys, the Dyers, the Cloughs, the Bushes, the Fords, the Northcrosses, the Youngs, the Hargraves, the Waltons, and the Greenleafs.

Elsie (Clough) Hart (1889-1975) attended West Orange School for five years in the late 1890s. In a 1970 interview she recalled:

“Oh, that was a darling little school almost on the corner of La Veta and Flower streets.... [Our teacher] was a wonderful person; she did more things for us ... her name was Alice McCarty. My father and Mr. Dyer just loved to help Miss McCarty get ready for Christmas. Papa would cut one of his cypress trees and take it over to the schoolhouse and set it up, and we had a big Christmas tree. All the parents and all the kids were there. I suppose there must have been thirty in the school.... I remember one time . . . I was the littlest one in school and Herb Sutton was a great, big tall guy in the Fifth grade, and I was in the First grade. They decided to play crack-the-whip ... and Herb decided that I was the one who was going to be on the end. Oh, they played crack-the-whip and I just rolled through the gravel and my whole face was practically gone. We used to have fun.... We just went through the Fifth grade down there. That’s all they had. Then we were big children and we had to go to the Orange School.”

Elsie Hart’s sister, Lena Mae Thompson, also spent five years at West Orange School. A few years before her death, she recalled:

“Up until the Fifth grade we went to the little West Orange School ... it was a little, one-room schoolhouse out there. And up through the Fifth grade they went there because it was too far to walk into Orange. But after that they had to walk into Orange to the one and only school there.”

(Ironically, despite these concerns about the long walk into Orange, both of the Clough sisters attended Kindergarten in Orange before starting at West Orange -- walking several miles back and forth each day.)

“When I was there,” Lena Mae continued, the West Orange School “…was just one little room. And I think there were two other kids in my class ... we had those five grades all in one room, and I thought I was pretty smart. I thought I was ready to go into Second grade when I was in the First, because I’d heard everything that they did – their lessons. The teacher would go from one class to the next and she’d have the kids come up and sit in front, probably three or four to a class. And I learned geography and a lot of stuff. I thought I knew everything before I even got into that grade because I would listen to the other kids.”

The students sat in the old style desks, with the seat attached in the front to go with the next desk on ahead of it. Lena Mae recalled that the students sat boys on one side of the room and girls on the other -- and that they even had separate doors to do in and out.

“[There was] just one teacher,” she continued, “…Miss Alice McCarty. And she lived way up on Cambridge Street between Walnut and Collins ... she and her father lived there together and she would ride her bicycle clear down there to the school and struggle with us kids all the time. She had some awful strict laws, and every night before she would let the little First and Second grade kids go home at 2 o’clock, she would ask the, ‘Did anyone throw a rock?’ That was one thing; we were never to throw a rock or clod. And ‘Did anyone speak out of turn?’ Did we talk when we shouldn’t talk in class. I don’t remember all the rules she had, but if any of us had done any of the things we shouldn’t we were kept for 15 minutes longer....

“[But] she was such a wonderful person that when Christmas came ... she got a gift for every one of us kids. And I can remember my sister ... they were all girls in her class, and she dressed a doll for each one of those girls -- made the clothes by hand! And when the mothers thanked her and complimented her she said ‘You don’t know how many times I sat up till midnight making the clothes.’ Lace on the underwear and such as that! They were dressed completely. She made little hats for them. They were just little dolls, not more than eight inches tall, but she dressed all of those dolls. And since she knew I was interested in plants, she let me have a little garden in the back [of the School]. I don’t know where she got the hoe, but there was a hoe there, and she let me hoe up and plant my initials in radish seeds. I made my initials in the ground and then put radish seeds in so when they came up there were my initials in my little garden ... L.C.”

Today, the only surviving student from those early one-room school days at West Orange is Bill Dyer, now 94. [Bill Dyer died in 1998 at age 101.] He entered West Orange in the fall of 1902 and went there for three years. His first teacher was also Alice McCarty, followed by Belle Jennings, and then Myrtle Parker. Jennings he recalls very well. He says that more than 20 years later, he stopped in where she worked and asked to see her and that she came rushing out of her office, “she remembered my voice after 20 years!”

Beginning around the time Dyer was born, his mother took on the job of cleaning up at the school. Curiously, the School District records almost always show the salary going to his father, but Dyer is positive it was mother who “used to walk down there about half a mile. She’d go there and clean it up. I don’t remember my dad ever working down there. I know she did.”

By the time Bill Dyer started attending West Orange School, the number of students there was already dwindling. By 1903 there were only about 15, and the numbers apparently continued to go down from there. Finally, he recalls, “there weren’t any more kids down there so they had to close it up and move [us] to Orange. So I started my Fourth grade in Orange.”

The teachers who taught in that original one-room school were an interesting group of women. They worked hard -- teaching five grades all at once -- and yet usually were paid less than the teachers in town. Those first teachers were:

Luella Bryan (1890-93, 1895-96)

Clara McPherson (1893-95)

Alice McCarty (1896-1903)

Belle Jennings (1903-04)

Myrtle Parker (1904-05)

Luella Bryan was one of a large family of girls, several of whom worked as teachers (in fact, in the fall of 1892 when Bryan took a short leave of absence, her sister Molly took over the teaching duties for her). Besides her skill as a teacher, she was also something of an artist, occasionally exhibiting her sketches around Orange County.

At the end of the 1892-93 school year, Luella Bryan decided that she did “not desire her place for the coming year,” and Clara McPherson was hired in her place. Bryan later did return to West Orange for one more year in 1895-96, and at the end of that term the School Board was visited by “a delegation from West Orange, consisting of Messrs. Northcross, Clough, Dyer and Murrill, [who] appeared before the Board to ask for the re-appointment of Miss Luella Bryan in their school.” But for reasons that are not stated, Bryan did not return, and Alice McCarty was hired to replace her. Sometime after that, Bryan left Orange and went to live with relatives in Hollywood. She died there on November 2, 1914 at the age of 47.

Clara McPherson was the daughter of William G. McPherson (1830-1908), an early Orange County settler (and a relative of the grape-growing McPherson brothers who founded the town of the same name between Orange and El Modena in 1886). Clara McPherson taught just two years at West Orange, and then retired from teaching. Her reason? On June 20, 1895 she married R.W. Jones.

Her new husband was then serving as the manager of the 800-acre Hewes Ranch south of El Modena – the largest ranch in the area. David Hewes, the owner of the property, had made his fortune during the California Gold Rush as a San Francisco contractor and investor. Hewes is also remembered as the donor of the “gold spike” used at the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Jones later had his own (decidedly smaller) ranch in El Modena, and for many years owned and operated the local water company there. The tall Victorian farmhouse which he and Clara called home for many years still stands (though it has since been moved to a new location). Clara (McPherson) Jones lived until 1948.

Alice McCarty was born in Missouri in 1875 and came to Orange with her father in 1877. She was a graduate of the Los Angeles Normal School (now UCLA) and apparently taught briefly at the Aliso School (near El Toro) before taking over at West Orange in the fall of 1896. Her teaching career also came to an end when she got married; but on the other hand, it was probably through her teaching that she met her future husband -- Kellar Watson.

In June of 1902, Kellar Watson (the founder of Watson’s Drug Store in Orange) was appointed to fill a vacant seat on the Orange School Board. Soon after, he and McCarty were seeing a great deal of each other. Lena Mae Thompson, one of her students, recalled:

“[Miss McCarty} had a boyfriend. It was Kellar Watson ... the original owner of Watson’s Drug Store. He would come around sometimes and get her with his horse and buggy and put her bicycle in the back. And we’d all stand around and look. We heard he had a diamond ring -- it was rumored he was rich, he had a store... and they couldn’t have two words together without all us kids huddling around ... they probably just loved us kids.”

Alice McCarty submitted her resignation as West Orange teacher in July of 1903, and Watson retired from the School Board that same month. Before the end of the year, the two were married. They lived the rest of their lives in Orange. Alice (McCarty) Watson died in 1933, and her husband in 1943. Their only son, Kellar Watson Jr., who later ran the drug store for many years, still lives in Orange. [He died in 1999.]

Belle Jennings taught for just one year at West Orange School (1903 - 04). She had been born in 1882, and came to San Diego with her family in 1887. She attended high school and college there, then shortly before her graduation, she left to take a teaching job at the Pala Indian School in northern San Diego County.

After leaving Orange, Jennings married William Benchley of the Benchley Fruit Co. They lived in Fullerton for several years, where Belle Benchley became the first woman to serve on that city’s School Board (1919-24). Unfortunately, the couple divorced about that time, and Belle Benchley moved back to San Diego.

In October of 1925 she secured a position as a bookkeeper at the San Diego Zoo -- then a small, shabby collection of caged animals. Within a few years, she became Executive Secretary, then Manager, and finally, in 1941, Director of the Zoo. Under her leadership, the San Diego Zoo grew into one of the world’s most famous institutions. Though she retired in 1963, she continued her association with the Zoo right up until the time of her death in the early 1970s.

Her successor at West Orange, Myrtle Parker, was less prominent. She also came from a family of teaching sisters, the daughter of Millard Parker, who served as the Tract Agent for the young town of Orange in the 1870s. Parker would also have the unhappy distinction of being the last teacher at the original West Orange School.

As the 20th Century began, the enrollment at West Orange School was drifting away. At first, the School Board did not seem overly concerned. In fact, in 1903 they even considered moving the Fifth graders to Orange and leaving only four grades at the school.

Eventually, the enrollment fell to the point where the cost of a separate school for West Orange could no longer be justified. Strangely, the School Board Minutes are silent on the decision to finally close the school; but it seems that June 8, 1905 was the last day of classes.

Perhaps the closure was presented as just a temporary move, because in the fall of 1906, when the Board began discussing selling off the old school building, the parents of West Orange began a fight to save their school. On September 6th the School Board held a special meeting “with the citizens of West Orange at [the] residence of Mr. Dyer. Present [were Trustees] Morrison, Brown and Briggs, also about 20 citizens. A discussion of the proposed sale of the West Orange School and grounds, as authorized by the District meeting of August 25th, 1906, resulted in an apparent disapproval of the sale by all citizens present. On motion by a citizen it was voted by all West Orange citizens present at the meeting to ask the Board of Trustees to open the West Orange School and establish a 5- grade school.

“On motion by Briggs,” the minutes continue, “seconded by Brown, it was decided to open the West Orange School on [the] condition that the citizens of West Orange pledge an attendance of not less than 25 pupils for the school year.”

This was a pretty small victory for the parents of West Orange, as it seems unlikely they could have scrapped together the required number of children. But even that small hope was lost five days later when the Board reversed themselves and decided “West Orange School can not be opened.” The reason given? “No funds.”

That was really the end of the original West Orange School. The building was sold off in 1910 (and later used as a barn, according to some old timers) and the District finally sold the lot in 1914.

West Orange Rides Again

Southern California’s growth is often traced through a series of real estate “booms” – periods of rapid growth and fast-paced development. The original railroad through West Orange was begun during one such boom. The first West Orange School was built at the tail end of another. After the tensions of the First World War began to fade away, Southern California began to warm up for a new boom, and once again West Orange would benefit from it.

West Orange was growing during those years, with the first residential tracts being laid out and a few businesses beginning to pop up along Main Street (which was then the route of State Highway 101). As the growth continued, it was decided to annex some of the area east of Main Street into the City of Orange (the original 1888 City Limits had stopped at Batavia). About the time the annexations began, the drive for a new West Orange School was kicked off. The Orange Daily News of September 1, 1923 gives some of the details:

“Education forward! Orange citizens, with the educational welfare of the city at heart, last night expressed themselves in these words when, at a mass meeting, they gave the Orange elementary school board authorization to purchase a tract in the ‘west end’ as a site for a new grade school.

“As a result the board today was preparing to launch an immediate investigation to procure a desirable site for the proposed new institution which is to serve the fast-growing West Orange district.... At the meeting last night, held at the Intermediate School, Orange voters, attending in fair-sized numbers, gave the project their unanimous endorsement. After the matter had been thoroughly discussed, [former mayor] F. L. Ainsworth introduced a motion, which was hurriedly seconded by F.E. Wilson, authorizing the board to purchase the school site.”

The cost of the site, and a four-classroom building, was estimated at $40,000; and the proponents were in hopes of holding a bond election to raise the required funds before the end of the year.

Before the month was out, five acres of land were purchased from William Kenyon, a local rancher. The tract was located along the south side of the proposed extension of Almond Avenue (which then went no further than Batavia) near where Pepper Street would join it. At that time the land was planted to orange trees, which the district planned to care for (and sell the fruit from) until the new school was completed.

By then it had already been agreed that a six-room school would be needed to meet the needs of the area, and the cost of the project was revised upwards accordingly to $70,000. The bond election to cover the cost of the new school was held on October 27, 1923. The turnout was small, but the vote went solidly for the new school. “Orange,” said Orange School Superintendent George Sherwood, “is to be congratulated upon having such a fine attitude towards the training of her future citizens.”

Next, plans had to be drawn and construction bids solicited. The final contract was awarded in April of 1924. That same month another 110 acres in West Orange (including the school site itself) was annexed to the city.

Construction kept right on schedule and the new building was ready for the start of school in September of 1924. Built of brick, it consisted of six classrooms built around three sides of an inner courtyard. Two of the rooms were arranged to open up into one long auditorium. There was also an office, a library, and a teachers’ room. The building faced onto Almond, on the site of the present campus. According to the Orange Daily News:

“The setting is ideal, the handsome brick structure being situated amidst orange and walnut trees. The small children will have the walnut trees for their playground, it was declared, while the older pupils will have a playground cleared for them at the south end of the tract.”

The new West Orange Elementary School opened for classes on September 15, 1924. There were 151 students in six grades, and six teachers:

Edna Watson (Kindergarten)

Lotta Brandon (First grade)

Margaret Ball (Second grade)

Alice Heil (Third grade)

Marjorie Atkins (Fourth grade)

Ruby Jeffers (Fifth grade)

Besides her teaching duties, Lotta Brandon also served as the school’s principal -- a job she would hold for the next 20 years. In 1990, only one of these women is still living, Margaret (Ball) Martin, now 95 years of age. She taught at West Orange for a total of 32 years, finally retiring in 1956.

Another early West Orange teacher still living today is Madeline (Clarkson) Witmer, who taught there for nine years, beginning in 1928. She recalls:

“We were happy to be placed at this modern brick building (the best around), surrounding a cement courtyard with a stage, library, teachers’ room and kitchen at one end. Benches were placed along the two sides of the courtyard so the children could sit there to eat their lunches.... Margaret Ball ... [was] there when the school was opened ... she said the building was placed right in an orange orchard.... The bus run by Mr. Arrowsmith was a great help to those who lived a bit out in the country.... Miss Rachel Williams was the music supervisor who came once a week. Miss Wheeler, art overseer, also came each week. Miss Vera Jones, school nurse, came occasionally. Mr. Michael was our very fine janitor for years, who always got plenty of help from students on special projects.

“At first we had a yearly [Christmas] program with all classes participating in costumes. Then we began taking the children to the high school for the Christmas pageant.... During the baseball season, teams from the other schools would come after school to play our team of 4th and 5th graders....

“West Orange had a very nice class of students who came from good homes with interested parents.”

During Mrs. Brandon’s tenure as principal, West Orange established itself as a solid part of the community, with quality teachers, a growing enrollment, and an active PTA. Some of the teachers from those years include Vesta Tracy, Helen Estock, Helen Lush, Margaret Babcock, and Helen Todd. And by 1942 West Orange could boast the highest enrollment of any local elementary school -- 203 children.

As for West Orange’s chapter of the national Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), it was founded the same year that the new school opened by Muriel Squires, and at times had as many as 90 members. They raised money through everything from rag drives to ice cream sales to purchase needed supplies for the school, held regular meetings and programs, and sponsored both a Cub Scout pack and a Girl Scout troop.

Sometimes their efforts also reached beyond the school grounds. During the Depression of the 1930s PTA funds were occasionally used to quietly assist local families in need. During World War II, they turned to promoting Victory Bond sales, and even held a “Jeep Day” in 1943 to help purchase “some part of a Jeep” for our armed forces.

But the real driving force at West Orange School remained Lotta Brandon. Some idea of her views on the role of the school in its community can be seen in this note which she sent home to parents in the fall of 1933:

“We are together again in a new school year, united in a common purpose -- the education of our children. They have come to us and taken hold of school work with an enthusiasm that is thrilling.

“May our lives be sincerely dedicated to their immediate future. May we so help them that their future progress will be steady and true and bring them joy and real satisfaction in their own work -- a confidence in their own ability.”

“Mrs. B.,” as she was known, was loved by students and faculty alike. The PTA minutes speak of her “very gracious and pleasant manner.” She was born Lotta Hayward in Fallbrook, California in 1883, but her family soon came to Orange where she lived until her marriage. She began her teaching career around 1908, and came back to Orange in 1922 to be a part of the first faculty at the new Maple Avenue School. Her first marriage ended in divorce, but in 1944 she married Lewis Thompson, Orange’s City Water Superintendent. Pauline (Thompson) Simpson, Thompson’s daughter from his previous marriage, was also a local teacher. She first met her father’s future wife in 1934 and recalls the good-natured rivalry that ran through Orange’s elementary schools in those days:

“There were three principal elementary schools at that time -- Center Street, Maple Avenue, and West Orange -- and the principals were great rivals -- Matie Danneman at Center, Iva Lee at Maple and Lotta Brandon (Mrs. B.) at West Orange.... Mrs. Killefer was principal at the Killefer School, but she was not a party to any rivalry.”

But Brandon’s real struggle came in 1944 when Stewart White, Orange’s new Elementary School Superintendent, decided that it was time to shuffle his principals around and so after 20 years – and much to her displeasure -- Lotta Brandon was transferred to Center Street School and Iva Lee came to West Orange. After just one year, Brandon resigned as principal of Center Street, though she continued to teach there until the end of the decade.

After her retirement, Lotta and Lewis Thompson continued to live in Orange, though they took many automobile trips around the country in the 1950s. In 1964 they moved to Reedley, California, where Lewis Thompson died in 1966. Lotta then went to live with a daughter in Oregon where she died in 1983, shortly after celebrating her 100th birthday.

Brandon’s successor at West Orange was Iva (Reeves) Lee, another long-time Orange teacher. She served as principal (and also taught) at West Orange until 1948. Her niece, Eugenie Lee, recalls:

“When she was principal of the school she always taught the first grade. She was an excellent teacher. I know she taught at Center St. School and later at Maple Avenue School (where the Baptist Church is now located). I always did child care during PTA days at the school when she was principal at Center, West Orange, and Maple....”

Lee was followed by James Gable, who had taught at Orange Union High School for several years (in fact, he and his wife wrote Orange High’s alma mater in 1941). Gable also had classroom duties besides his job as principal, teaching the Fifth grade.

Growth, Growth and More Growth

During Gable’s eight years at West Orange a number of changes took place -- many of them in response to the incredible wave of growth that was beginning to sweep over Southern California during the post-War years. When Gable arrived there were around 200 students at West Orange School, and seven teachers. Before he left, both those numbers would double.

To meet the demands of this growing student body, three new classrooms were added west of the brick school in 1949 which are still in use today. In January of 1950, the Kindergarten, First and Second grade classes moved into these new rooms leaving the Third, Fourth and Fifth graders in the old building. Besides increasing the capacity of the school by 50%, the new wing also left space in the old building for “a school library, a PTA meeting room, a nurse’s office, principal’s office and a special services room, where movies can be shown.”

But still more and more students kept arriving (including the addition of Sixth graders in 1953), and before long West Orange was again overcrowded. The opening of Sycamore Elementary School in 1956 eased some of the crunch, but as early as 1953 the PTA began asking the School District for more new classrooms.

But overcrowding was a problem throughout the Orange Unified School District then, and the School Board first had to find funds for the construction of a number of badly needed new schools. To buy time, West Orange began to operate on Double Session in the fall of 1953 and continued on that schedule on and off into the early 1960s. Double Session simply meant that students came in shifts, half in the morning and half in the afternoon. In 1956 the PTA minutes explained:

“Children who live south of Chapman avenue, west of the Santa Fe railway and east of the Santa Ana River, [are] to attend morning sessions. Children who live on the north side of Chapman avenue and west of the 101 Freeway [now the 5] to attend afternoon sessions.”

1956 was also Jim Gable’s last year as principal of West Orange. He was followed by John Miller, who was the school’s first full-time (non-teaching) principal. Miller had come to Orange in 1954 and taught one year at West Orange before moving on to become a junior high school principal. But after a year he was back at West Orange as principal, and stayed on for the next five years before leaving to take over as Superintendent of the Yorba Linda Elementary School District.

Miller pushed for many improvements at West Orange, including planting grass on part of the playground (he formed the “West Orange Bermuda Association” to raise the funds needed) and laying blacktop over the rest, along with new lighting and emergency hardware for the old brick school.

The 1950s also saw a couple of annual events become West Orange traditions. Chief among these were the School Carnival in the fall, and the end of the year All-School Picnic in June -- a family potluck affair, held for years in Santiago Park. By 1960 West Orange had also adopted the “Warriors” as the name for their school teams.

As the ‘60s began, West Orange had 16 teachers, plus a principal, a secretary, two custodians, and over 430 students still on Double Session. Talk of building new classrooms was increasing every year (especially when bond elections were coming up), but actual construction was still a few years away.

Finally, in 1964, ground was broken for a new West Orange School -- part of a $25,000,000 building program throughout the district. The new classrooms and office building were completed in April of 1965, and students and faculty gladly moved in. The new campus faced out onto Bush Street (which was named, coincidentally, for Charles Bush, who led the drive for the original West Orange School in 1890). Very shortly after it was completed the 1924 brick school was leveled. Today the only remains of it are a few bricks (bought from the wrecking company by the PTA) that were used to build a planter box in front of the new office.

Helen Oliver, who taught at West Orange for 26 years, beginning in 1955, wrote out some of her recollections of these years at the time of her retirement in 1981:

“My memories of 26 years at West Orange are all so personal, I’m not sure what would be of interest to others. Certainly the old brick building with its Spanish architecture, arches along the corridors in front of the upper-grade classrooms, the beautiful hardwood floors in all the rooms, and the inestimable value of cloak rooms for not only stashing unmentionables things, but, on occasion, unmentionable disciplining as well.

“We always had out Christmas programs on the ‘stage’ outside the office, hoping, as we do now, for good weather. Mostly it was, but there was the year that we had painstakingly taped large paper backgrounds [up] for the musical Christmas cards we were using ‘on stage ‘ when a big Santa Ana Wind sneaked around somehow and sent it all tumbling down in the middle of one musical-card presentation.... And of course there was the year our manger scene held an incredulous Mary as Joseph’s upset stomach got the better of him and he just couldn’t hold it in!

“The big center between the [old] buildings was to be painted in resplendent form depicting the states of the union, but by the time the students got to Kansas, they’d about run out of room, so the map wasn’t exactly drawn to scale....

“Building the new rooms facing Bush [in 1964-65] meant painting over the visible windows in Rooms 41 and 42 so that at least the visual if not the audible distractions on the building site were at a minimum. But we had many a field trip to look over the building operation that year....”

The PTA was going through some slow years in the early ‘60s, and in 1964 even chose to let their membership in the national organization lapse and just functioned as a local parents’ group. They also dropped their sponsorship of any Boy Scout, Cub Scout, Girl Scout or Brownie units for a time. But as the decade progressed, the group came back strong, and again began making all sorts of gifts to the school -- curtains, risers, jungle gyms, audio-visual equipment, teaching materials and more.

New classrooms continued to be added over the coming years as well, including the “multi-purpose” buildings, where four classrooms can be opened into one. Other temporary buildings have also been moved on to the campus which have helped keep West Orange from becoming overcrowded, even with an enrollment that passed the 500-mark in the late 1970s. During this same time the number of minority children who attend West Orange School also increased, posing new challenges for both teachers and administrators alike.

West Orange School Today [1990]

But West Orange School has continued to meet these challenges, and deal with them quite successfully. In recognition of the school’s efforts, West Orange was selected as one of 120 winners of the National Distinguished School Award for 1987- 88. The faculty was quick to credit Principal James Barton for his contributions to this achievement. At the time, the Orange City News noted:

“West Orange has a cohesive staff that works well together. Dr. Barton supports and encourages both the staff and the students, said school secretary Robbie Santillo.

“One challenge for the staff at West Orange is the large turn over in children. During the year some chairs in the classroom may be used by four or five different children -- children whose needs are especially great, Barton said. ‘We help children believe in themselves, to rise above their level in life.’ Dr. Barton credits his staff and others in the district for many of the ideas used at West Orange....

“‘If I had to choose one thing in a school to work on, it would be school climate,’ Barton said. ‘It ranks at the very top.’ If a school is well-organized and disciplined, with clear expectations and enthusiastic, courteous relationships, everything else will fall into place. He finds that children will learn skills and responsibility, and test scores will go up in such an atmosphere.”

Today, with an enrollment of over 550 students from Kindergarten to Sixth grade, West Orange is continuing its commitment to excellence. In her recent report to the school’s parents, 1990-91 Principal Mary Elaine Kunz states:

“West Orange Elementary School believes that our mission is to provide quality programs with an emphasis in developing basic skills, social responsibility and citizenship, feelings of self-worth and an awareness and appreciation of our American heritage and other cultures.

“West Orange School celebrates its Centennial in September, 1990.... During [the last 100 years] Orange has experienced tremendous changes both in terms of population and urbanization of our citizens. Through World Wars, depressions and recessions, technological explosions and social changes, West Orange has continued to serve our children well. Programs have reflected the needs of our students and community over the years. Today we face many exciting challenges such as student transiency, language and cultural diversity, effects of single parenting, poverty, low student motivation and the need to prepare our students to participate in a technologically complex society.

“The Staff of West Orange School accepts these challenges and works hard to meet them daily. We are proud of our school and its heritage, point with pride to our recent accomplishments and look forward to the future with enthusiasm and optimism.”

West Orange Principals, 1890 - 1990

Luella Bryan, 1890-1893

Clara McPherson Jones, 1893-1895

Luella Bryan, 1895-1896

Alice McCarty Watson, 1896- 1903

Belle Jennings Benchley, 1903-1904

Myrtle Parker, 1904-1905

(School closed, 1905-1924)

Lotta Brandon Thompson, 1924-1944

Iva Reeves Lee, 1944-1948

James Gable, 1948-1956

John Miller, 1956-1961

Del Penney, 1961-1965

Richard Blakemore, 1965-1971

Paul Jungkeit, 1971-1972

Glenn Ditmore, 1972-1977

Ken Neisess, 1977-1982

Art Munoz, 1982-1984

Dr. James Barton, 1984-1989

Mary Elaine Kunz, 1989-

Acknowledgements

This all-too-brief history of West Orange is drawn from many sources. In place of a full listing I will mention a few of the most important: The early records stored at the Orange Unified School District office have always been cheerfully made available to me. Saved from the brink of destruction were many of the records of the West Orange PTA dating back to the 1930s. The files of Orange’s newspapers (available on microfilm at the Orange Public Library) were also useful. Of special value were the Orange News of 1890 and the Orange Daily News of 1923-24. And, of course, a project like this could not be done without the recollections of our old timers. I am especially indebted to Bill Dyer, Eugenie Lee, Madeline Witmer, Pauline Thompson, and the late Lena Mae Thompson, whose memories first introduced me to the early days of West Orange School. I have also received encouragement from three recent West Orange principals -- Ken Neisess, James Barton and Mary Elaine Kunz, all of whom have been interested in seeing this Centennial celebrated in proper style.

West Orange School, 1924-1965 (courtesy the Orange Public Library and History Center).