A stage coach pauses in front of the Planters Hotel in Anaheim, circa 1882 (courtesy the Anaheim Public Library).

Stage Coach Days in Orange County

It is difficult today to picture Orange County as a part of the Old West, but it has its share of pioneer tales. In the second half of the 19th century, stagecoaches were a common sight on local roads. They carried passengers, mail, and freight, connecting the county with the outside world.

Despite some later claims, the famed Butterfield stages did not pass through what is now Orange County, but local travelers could board the stage in Los Angeles, bound for San Francisco, St. Louis, or points between. Instead, it was the various Los Angeles-to-San Diego lines that were the most important here. The first was established in 1852 by Phineas Banning and D.W. Alexander. A year later, there were three competing lines. At the end of the decade, Paul & Chapman were providing bi-weekly service via “Los Nietos, Santa Ana, San Juan Capistrano, Hot Sulphur Springs, and San Luis Rey.” (Los Angeles Star, June 4, 1859). “Santa Ana,” in this case, meant the old Yorba family settlement at Olive. It seems unlikely the stages detoured all the way up San Juan Canyon to reach San Juan Hot Springs (in what is now the upper end of Caspers Wilderness Park), but it is interesting to see that the springs were already a tourist destination in the 1850s.

The population was sparse in those days, and settlements few, so the early stage companies always hoped to secure the contract to carry the U.S. mail as something of a subsidy. This also helped the communities along the way to get their own post offices. Anaheim got a post office in 1861, barely two years after the first settlers arrived. Capistrano got one in 1867. William McLaughlin was the first postmaster and the stage stop was at his store. He was a stage man himself, running a line from Anaheim to Los Angeles in 1870.

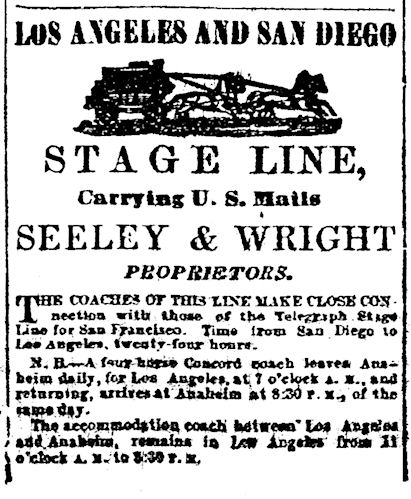

The best remembered of the Los Angeles-to-San Diego stage lines (or in this case, a San Diego-to-Los Angeles line) was Seeley & Wright’s Los Angeles & San Diego Stage Line, which was launched by Alfred L. Seeley of San Diego in 1868. A year later he took on Charles Wright as a partner to look after the Los Angeles end of the business. The Seeley & Wright made the run in two days, spending the night at San Juan Capistrano. The fare in 1872 was $16 each way. As this area grew in the 1870s, Seeley & Wright steadily increased their service, eventually running six days a week.

Being along a stage line was an important asset for any community (much as the railroads would be in later years, or freeways are today), and town founders in the early days were eager to secure a stop. William H. Spurgeon, the founder of Santa Ana, even had a new road built to convince the stages to run through his new townsite.

The principal stage road through Orange County in the 1870s basically followed the route of today’s Santa Ana Freeway (I-5). Besides stops in Anaheim, Orange, Santa Ana, Tustin, and San Juan Capistrano, there were a few intermediate stations as well. The Seeley & Wright changed horses at a small adobe southeast of Tustin (near Bryan and Browning today) sometimes called French’s Station but more often simply the Adobe Station. Water stops included the old Los Coyotes Adobe (on the grounds of today’s Los Coyotes Country Club) and Aguaje del Cuate, an important spring north of San Juan Capistrano at about Oso Parkway.

(Notice how none of our supposed “robber’s caves” and “robber’s roosts” are anywhere near this route.)

George C. Morrow (1835-1922) was the best known of the old Seeley & Wright stage drivers here, living for many years after in Villa Park. Interviewed by Terry Stephenson in 1920 he recalled:

“A man driving along now has a hard time making himself believe that the country is the same country. Then the whole country was covered with mustard. It was higher than a man’s head. In fact, a man on horseback could ride out of it and you’d never see him coming.”

“My regular drive called for me to leave Anaheim about dark. My first change of horses was at what we called the adobe station out on the San Joaquin ranch. The company kept a horse tender there. I’d take on fresh stock and go on to San Juan Capistrano, which was very much of a Spanish village in those days…. After changing horses, I’d drive on to Las Flores, where I arrived right along at 3 o’clock in the morning. I’d stay there until the evening of that day when the return trip was started, getting me back to Anaheim about 3 the next morning.”

(This was the old Marco Forster Adobe, which still stands on Camp Pendleton, not the modern community that has borrowed the name.)

“The man before me had a hard time of it, for he was always getting lost and off the road. The consequence was that he was late delivering his passengers and mail at Las Flores. All along the way then there were places where it was mighty easy to get off the road. People just traveled off across country by the most direct route. I had been over the road only once when I started out on my first trip of driving at night, and what I am proud of was that I got to Las Flores on time, and Seeley down in San Diego sent word back to ‘tell that fellow not to drive his horses so hard.’ I wasn’t driving hard, but I didn’t lose any time off the road, no matter how dark or stormy it got. I sent back word that I let the horses walk through sand, but by gum they had to trot when the road was good….

“If the stage was loaded right, it was as easy riding as a buggy, but if it wasn’t loaded right, it had antics all its own. If there was too much baggage on the rear boot, the driver’s seat and front boot were thrown up in the air, and if it was too heavy in front the rear end flew up.” The stage coaches could carry up to nine passengers inside and two outside, “but we often loaded twelve or thirteen, just as many as the passengers would stand without roaring.” The mail was carried in a locked leather pouch, but every postmaster along the way had a key, including Tustin and San Juan Capistrano. (Santa Ana Register, January 31, 1920)

There were a few hold-ups in the early days. Tustin pioneer John Dunstan told Stephenson, “There were hold-ups even after I came here in the seventies. I remember the winter that the stage was held up three different times in the wide gulch this side of El Toro. The bottom there was covered with heavy brush, and it made a mighty good place for the bandits to ride in, hide their horses and wait for the stage.” (Register, January 31, 1920)

With the coming of the railroads, stage service began to decrease. Typically, the stage lines would begin where the railroad tracks ended. After 1877, that meant Santa Ana; San Diego-bound stages ran south from there until the Santa Fe’s coast line was completed in 1888.

There were a number of shorter, local and connector lines as well. In 1875, B.F. Smith offered daily stage service (except Sundays) from the new Southern Pacific depot in Anaheim to Orange and Santa Ana. He also made runs to Newport Beach when McFadden’s steam ship arrived. Another 1870s stage ran from Anaheim to Anaheim Landing, near Seal Beach, and a short line connected Orange with the Southern Pacific station at West Orange.

In 1880, you could ride from Santa Ana to Riverside via the Santa Ana Canyon. In 1881, stages were running between Santa Ana and Wilmington: “Mr. J.E. Preston gives notice that a stage and express will leave Santa Ana for Wilmington, via Garden Grove and Westminster, on Monday next at 10 A.M., and every succeeding Monday, returning the following day. Stage office at Spurgeon’s store. Public patronage respectfully solicited. Commissions carefully executed. Orders left at Spurgeon’s store.” (Santa Ana Herald, August 13, 1881)

During Silverado’s brief boom in 1878 there were at least four stage lines in operation – two from Santa Ana, one for Anaheim, and a fourth from Los Angeles: “The proprietor answers to the suggestive name of Walker. The distance is fifty miles, the fare is $3, and it is proposed to run the stage three times a week. One station is at Hindesville and the other at Keith’s near the picnic grounds [today’s Irvine Park]. Few people nowadays care to travel such a distance by stage, even to save a dollar or two. Nearly all the travel to the mines is by way of Anaheim. The stage which leaves Anaheim every morning seldom has less than three or four passengers.” (Anaheim Semi-Weekly Gazette, September 18, 1878)

Laguna Beach was connected to Santa Ana by stage during the real estate “boom” of the 1880s, with coaches running all the way south to Arch Beach. Later, Aliso Canyon pioneer Joe Thurston recalled, “Mr. Farman, who was an old stage driver, came in with a typical stage outfit, a real old stage coach with leather rockers in the place of springs, and he kept that outfit running for many years and apparently made a living out of it…. He was quite a character and used to tell about his experiences on the frontier.” He used to say, “There ain’t no balky horses, but there’s plenty of balky drivers.” (South Coast News, June 21, 1935)

Perhaps the last stage line in Orange County also ran down to Laguna Beach. It met the trains at either Irvine or El Toro. Joseph Yoch, owner of the Hotel Laguna, replaced the stagecoaches with an auto stage in 1902.

(Anaheim Gazette, May 2, 1875)