The Silverado Mining Boom of 1878

Mining has never been particularly profitable in the Santa Ana Mountains – but that has never stopped the prospectors and promoters from chasing after their dreams. There have been flashes of excitement up and down the range since the 1860s, but the biggest mining boom in the mountains was in 1878, when Silverado first burst on the scene.

Who first found silver ore in the canyons is disputed. There is some evidence that Mexican miners were working the Cañada de la Madera (Timber Canyon) as early as the 1850s. The first known claims were staked in August of 1877, and the first newspaper report went out that September. But the news had little impact. At the time, the big story was the new Black Star coal mine, which gave its name to that canyon. It was not until early 1878 that things really began to stir in the canyon.

Silverado had many of the elements of a classic mining boom. The ore was shallow – in some places the veins were visible right on the surface. It was close to the railroad and settled towns including Anaheim, Santa Ana, and Orange. The region was just coming out of “dull times” (as they said in those days) brought on by the drought of the mid-1870s. And there were a few men here who just knew they were all going to get rich.

There does not seem to have been a single event that set off the boom. News of new claims and rich assays had been trickling out of the mountains in the last weeks of 1877. By January 1878 rumors had turned into reality with the first shipment of ore. A townsite was laid out that month and by summer the boom was going full blast. Prospective prospectors and would-be miners took to the hills. A few even knew what they were doing, having worked in the mines of Northern California and Nevada, but most were local ranchers and farmhands. It was, as historian Jim Sleeper noted, a “good excuse to get away from the farm and family for a few weeks.”

In February 1878 a mining district was formally organized, giving local prospectors a place to register their claims. Curiously, it was named the Santa Rosa Mining District (Jim Sleeper suggested that this might be an alternate name for Modjeska Peak in the hills above), and Pharez A. Clark was elected District Recorder. It Clark who gave Silverado its name when he laid out the townsite at the mouth of Pine Canyon, not far from today’s Maple Springs Visitors Center.

Most of the claims were crowded along the hills above Pine Canyon and its tributary, Half Way Canyon. As in many mining areas, there are different versions of just who made the first “strike” here, but the earliest sources all pretty much agree that H.C. Purcell and G.F. (“Goldie”) Slankard found the first indications on August 5, 1877. They were joined in staking their claim by Henry Cassidy (also spelled Cassida) and Thomas (“Hank”) Smith. They called their claim the Southern Belle.

The usual story is that these men were out hunting in the canyon when one of them spotted a piece of “float” (loose, ore-bearing rock). They followed other pieces up to a rock ledge where they staked their claim. Once word got out, close on their heels came J.D. Dunlap, Cash Harvey, Henry Knapp, and others. These three would all play prominent roles in Silverado’s future.

As for the original discoverers, Purcell seems to have sold out in August of ’78 (making him about the smartest of the bunch). “Goldie” Slankard also got out early and went on to other mining fields in Arizona.

The first newspaper report of the new silver strike seems to have appeared in late September 1877, reporting an assay of $60 to the ton. By the end of the year, the Anaheim Gazette thought enough of the story to send a reporter to the canyon. “These mines were discovered last summer by a party of gentlemen who made several locations which they have worked, and from some of which they have very encouraging prospects…. A ton of ore from the Southern Belle worked $53.50 in the California Reduction Works in San Francisco, and assays from the mine being worked by Thistlewaite & Co. have run into the thousands…. The coming spring will witness many important discoveries and developments in the Sierra de Santiago.” (1-5-1878)

Notice the difference between the assay figures of thousands of dollars in silver for each ton of rock and the actual returns of less than $60. The assayers would extract the metal from a small amount of hand-picked, ore-bearing rock and then estimate how much silver might exist in a ton of the same quality rock. But it was never that simple. Experienced miners and mining investors knew that, but reports of rich assays continued to pour out of the canyon.

The Boom Begins

By February 1878, papers further afield had picked up the story and hopeful prospectors had spread out over the hills. But the real rush didn’t start until a few months later. Throughout the summer of 1878 the Santa Ana Mountains were crawling with prospectors, staking claims with little regard to actual mineral showings. The procedure was simple enough: pile up some stones along the boundaries of a rectangle, 300 x 1,500 feet. Then write out a claim notice and put copies in all the rock piles (a metal tobacco tin was useful to protect it from the elements), then taken a copy down to P.A. Clark, who would collect a few dollars and record your claim. Now you had first rights to the ground and anything below it, all the way down.

“Everyone who visits the district seems to go clean daft,” the Anaheim Gazette reported (8-3-1878) “and become thoroughly saturated with the prevailing excitement. Claims are staked in the most absurd locations, regardless of whether the indications are good, bad, or indifferent. It is the fashion to own a claim; and in this as in other things, the dictates of fashion must be obeyed. One gentleman, who had conformed to the prevailing mania, and staked off a claim, told us with refreshing candor that he didn’t suppose there was twenty-five cents’ worth of ore within half a mile of his location, but he felt impelled by some subtle influence to stake off a claim.” “For ten or fifteen miles, in every direction from Silverado, claims have been taken up,” the Los Angeles Herald noted a month later. “...Hundreds of prospectors are scattered through the mountains.”

The excitement soon spread over the mountains as well, with Riversiders deciding they wanted a piece of the pie waiting just over the hill. But getting there could be grueling. A writer in the Riverside Press (9-21-1878) described the ordeal of a group of men who came up from the Temescal side (perhaps along Bedford Canyon) and started down from the divide: “There was no human track, but we obstinately persevered through miles of ascent and descent, with frequent patches of such tangled brush that we had to crawl on our hands and knees to get beyond it, clothes torn, hands bleeding, throats dry. We at last reached the new mining settlement by a final descent of a mountain side so steep as to be almost impracticable.”

P.A. Clark gave Silverado its name and was one of the leading figures in the area during the boom days.

District Recorder Pharez Allen Clark (1845-1891) remained the big man in town. Come to that, he was a big man anywhere, “a sort of infant Hercules who pulls down the scales at three hundred and twenty-five pounds, and who walks up to the Blue Light mine three times a day, without even starting the perspiration.” (Los Angeles Herald, 9-3-1878) “P.A.” (as he was known to family and friends) had lived in California since the early 1860s. It is perhaps not a coincidence that he had once lived in St. Helena, near California’s original “Silverado” (a play on the old Spanish name for rich gold diggings – El Dorado). In any case, the name is a hand-me-down, used in several Western mining areas over the years. Before coming to Anaheim in 1871 he had lived in Alpine County where he obviously learned a little about mining – and mine promotion. Anaheim historian Leo Friis considered him a “flashy operator,” Jim Sleeper noted that he always seemed to have some new sensation for the papers every time came down from the hills.

Once the rush was on, his townsite began to grow. In June, it had only four buildings, including Clark’s office and a boarding house offering beds and meals. A second boarding house appeared in July, along with two restaurants (which no doubt served liquid refreshment as well) and Cash Harvey’s stable and feed yard. The first stage service began that same month, coming up three times a week from Santa Ana.

“The town, although incipient, shows a good healthy growth,” the Anaheim Gazette reported on August 3rd. “The houses are not brownstone edifices, but they answer all practical purposes for which they are destined. Apparently there is one street – Main street – but Mr. Clark assures us that there are also numerous side streets, all duly named, etc. Clark & Co. have three houses of boards on Main st., used for boarding house, assay office, and residence. There is also a mill put up on Main street – a gin mill, Capt. Ruger proprietor. You see that commences to savor of a real old time mining camp of ’49. Next comes a butcher shop, which will be found a great convenience to the hungry miner, heretofore subsisting on bacon. On our way back we met teams loaded with goods for a store, to be commenced by Mr. Pierce from the [Gospel] Swamp. Mr. [James] Huntington’s residence lies on the southeast side of town, on Main street…. There are also two stage lines from Santa Ana – one daily and one running every second day.” The Anaheim stage began running later that month, with a line from Los Angeles added in September.

There were always more tents than wooden buildings in Silverado during the boom. In fact, during that summer many men didn’t even bother to set up tents and simply camped under the trees and brush. Others stayed at one of several boarding houses in town. The best known was the Gillett House. In September a correspondent of the Gazette noted, “It was our fortune to stop at the Gillett House, where we found every comfort and convenience. Mr. [C.G.] Gillett is an experienced hotel keeper, and his wife [Maggie] is an amiable lady, and has a knack of fixing up appetizing dishes for her guests. We liked her bread so well that we prevailed upon her to tell us how she made it. She gave us a recipe for making yeast, which we will publish one of these days for the benefit of our lady readers.”

New businesses continued to appear in September. A second store and feed yard, a blacksmith shop, a butcher shop, and two bakeries. Later came a fruit stand, a shoe store, and a growing number of saloons. “This place has taken another step toward metropolitan greatness by the establishment of a new and tony saloon,” the Anaheim Gazette reported on September 7th, “which was opened on Monday by a Mr. Walsh, of Los Angeles. A bright display of decanters and the articles usually to be found ornamenting a first-class bar, with pictures, chandelier, etc., comprise the interior fixtures of a large tent with the familiar words, ‘Sample Room,’ over the door. Silverado now has four saloons and the same number of clergymen; or, in mining parlance, ‘Gospel Slingers’ and ‘Gin Slingers’ are always to be found in the same ledge.”

And gamblers, the Gazette added – at least briefly: “Several gentlemen whose profession is Poker or Pedro have honored our city with their presence but a dull trade in their line deprived us of their protracted presence.” The first regular church services were held in October. “The audience was respectful and very attentive,” the Gazette noted.

In fact, Silverado was always something of a family town. “The population is composed in the main of farmers from the various parts of the country,” the Anaheim Gazette noted (9-18-78). “One meets familiar faces at every turn. Anaheim, Westminster, Santa Ana, Orange, Tustin, Newport, Downey and other towns in the county are largely represented, and when early winter rains give warning that the soil is once more ready for the plow, there will be a very general temporary abandonment of the various claims, unless, indeed, a mill is by that time established, and the ore is found to be as rich as is now supposed….

“The town of Silverado is as unlike a mining camp as could well be imagined. The presence of women and children has a depressing effect on the forty-niners, of whom there are not a few in camp. One of them was sitting in front of a saloon on Sunday, entertaining a small audience with reminiscences of his mining experience in early days. ‘We didn’t have any of them ar things about,’ said he, pointing the finger of scorn at a group of women and children, ‘we could git drunker’n a biled owl, an’ rip an’ tear around quite promiscus, but when a feller comes to this here town he’s got to keep his face clean an’ take his pizen like a sneak, ’count of them ar wimmin.’ Another cause of grievance to that ilk is the quality of the whiskey. Through a mistaken notion of the requirements of the camp, the saloon keepers all have a very good quality of liquor. This does not suit the Argonaut; indeed, it is one of his pet grievances that he cannot get the bug-juice of pioneer days – the kind, he explains, that used to knock a man half way round the block.”

In fact, there were so many children in town that P.A. Clark’s sister, Emma, started a private school in late August. An actual school district was established two years later, but by then the mining boom had shifted down canyon to Carbondale.

Still, in the minds of the earliest residents, Silverado was here to stay. They drew up a petition asking for a post office, which was approved in Washington on August 27, 1878. A year later, a township and voting precinct were established, giving Silverado a Justice of the Peace and a Constable to enforce the law.

Henry Knapp’s oft-quoted description of Silverado at its peak in late summer 1878 is still a good one. At that time, the town boasted “three hotels, three stores, seven saloons, two blacksmith shops, two meat markets, a select school, and all the other industries of a first-class mining camp. Town lots sold as high as seventy-five dollars each, yet nearly all the dwelling were canvas tents only, and the occupants of board shanties were looked upon as ‘bloated aristocracy.’”

Yet despite later, exaggerated figures, the population of the town never seems to have topped about 150, with perhaps a couple hundred more men roaming the hills or living in camps closer to their claims.

Mining Claims

Inside the Blue Light Mine, 1941. This photo was taken by a teenage Jim Sleeper (courtesy Nola Sleeper).

The hills south and east of town were busy all that summer. By September 1878 more than 280 claims had been filed. They were named for wives and daughters, animals and places, or simply sheer optimism. Besides the original Southern Belle and the famed Blue Light, there was the Keystone, the Alleghany, the Alabama, the Mammoth, the Eureka, the Continental, the Dunlap, the Flanagan, the Eli, the Mountain View, the Sunday Belle, the Alpha, the Santa Ana, the Fairview, the Florentine, the Orion, the Providencia, the Confidencia, the Ophir, the Alpha, the Emma, the Marion, the Southern Slope, the Sunny Slope, the Gold Hill, the Excelsior, the Bear Gulch, the Golden Rule, the Mayflower, the Pocahontas, the Warwick, the Wild West, the Pride of the West, the Mooreland, the Scorpion, the Grizzly (later renamed the Maggie, in honor of Maggie Gillett), the Wildcat, the Rough and Ready, the Montezuma, the Victoria, the Fautina, the Red Rock, the Phoenix, the Princess, and, of course, the Silver Belt, the Silver Prize, the Glittering Knight – and Pearson’s Folly.

The Grayback Lode, where the Dunlap, Flanagan and Blue Light Mines (among others) were located above Pine Canyon, got its name in a curious way. When one of the first prospectors came down out of Pine Canyon in 1877 he found a few “graybacks” crawling on him – that was what the Civil War soldiers called lice, but in the Santa Anas, one wonders if it wasn’t another blood sucking insect – ticks. The only hint of the origin of the Blue Light name is a mention of a seam of “bluish quartz” spotted in Pine Canyon during one of the earliest prospecting trips.

Many of these claims were never more than a few piles of stones marking the boundaries. Others were dug out here and there searching for signs of a vein. Many who found them stopped there, to await outside investors. Only a few began actually tunneling. Henry Cassidy and his partners opened up the Southern Belle to some extent. The Ophir, the Warwick, the Flanagan, the Florentine, the Mammoth, the Mountain View, and the Alpha all started tunneling during 1878, but none had gone much more than about 50 feet by the end of the year. The Rough and Ready sunk a 60-foot shaft, and the Southern Slope had an incline shaft down more than 50 feet. Even the Blue Light had just two adits (tunnels) totaling about 75 feet.

But even this limited amount of work took money. Where a prospect hole could be opened by pick and shovel and sweat; actual tunneling needed workmen, and explosives, and timbering, and ore carts, and tracks. And that was just the beginning. The ore-bearing rock then had to brought down from the mines on burros, hauled out the canyon by wagons, and shipped by rail all the way to San Francisco to be crushed and processed to extract the silver. What was needed were tramways to the mines, better roads out to the flatlands, a mill to crush the ore, and maybe – someday – even a smelter to process the ore right there in the canyon.

The great cry from Silverado, almost from the beginning, was the need of outside investors. At first, a few businessmen from Anaheim, Santa Ana, and the surrounding towns grubstaked prospectors and put up a little cash to help open up the mines. By August, mining companies were being incorporated to offer stock to outside investors. The first seems to have been the Florentine Mining Company, formed largely by Anaheim promoters. The Blue Light Mining Co., organized by J.D. Dunlap and others, soon followed. These two companies offer $1,500,000 worth of stock – but there were few takers. A mill was always ‘on its way’ – but never arrived.

Several things limited outside investment at Silverado. To lure big investors, Silverado first needed to show a profit – but to show a profit, the mines first needed more investors. Oddly, some believed that Silverado was also hampered by being so close to civilization. If it were off in some isolated desert wilderness, they argued, it would be easier to lure in investors, who had come to expect mines in places like that. What little ore did make it from Silverado to the smelters also proved difficult to process, particularly separating the silver from the lead that occurred in the same veins.

As is often the case, the rush to Silverado soon spawned other brief booms. Placer gold was found in Ladd Canyon, and silver and lead in Shrewsbury Canyon (today’s Harding Canyon) where a rival town of Santiago City was laid out. There were alleged tin strikes as well, but the most significant find was when coal was discovered near the mouth of the canyon early in 1878. A town dubbed Carbondale grew up there, near where the Rancho Silverado Stables are now located. All these new strikes also competed with Silverado for investors.

By October 1878, the Silverado boom had peaked, and began its slow decline. Every piece of likely ground (and some rather unlikely ground as well) had been claimed. A few tons of carefully selected ore had been shipped to the smelter in San Francisco, but the results were lackluster. Setting aside some of the exaggerated figures published in the papers, the most dependable numbers come from the testimony in one of the lawsuits over conflicting claims which showed one company had shipped 26 tons of rock north which had yielded on average just $150 a ton, before costs.

As winter approached, one by one the prospectors moved on, the amateur miners went back to their farms, and the real miners headed for the next big strike. Businesses closed, tents were folded, and Silverado faded. The Gillett House – the last of the boarding houses – survived a couple more years, and Cash Harvey kept his feed yard and stable open, but the boom was dead.

The Anaheim Gazette tried to put a good face on its demise in an editorial (10-5-1878): “The fact is, the mountains have been thoroughly prospected, and consequently no new discoveries are being daily and hourly reported. The crowd of idle and curious men who were drawn to the district in the early part of its history has departed, and all that remain are workers who are quietly but energetically tunneling into the mighty mountains, and have neither time nor disposition to keep up the undue and artificial excitement which pervaded the place a couple of months ago…. The fact that there is now comparatively little being said about the mines is encouraging. It is a sign that the men who are developing them are too busy to talk.”

The Last Gasp

There were still a few true believers who pushed on into 1880s. High on the list was Jonathan D. “Doc” Dunlap (1825-1904), a veteran of the Mexican War (1846-48) and almost a ‘49er (he was in El Dorado County by 1850). He had come to Los Angeles in the ‘60s and in 1868 was appointed a Deputy United States Marshal, serving for the next twenty years. He was widely known and had an excellent reputation as a lawman, a “man of iron nerve and sleepless vigilance,” the Los Angeles Times noted (12-17-1887), “who can neither be cajoled, bullied, nor bought.” He first visited Silverado in September 1877, just a month after the first strikes, on the trail of a criminal, caught the mining fever and staked his claim – the Dunlap. Later he acquired several adjoining claims including the original Blue Light.

No photos seem to have been taken during the boom days in Silverado (Anaheim’s only photographer set out to visit the mines, but his buggy rolled off the road, he broke his arm, and never returned). So the photos we do have all show later buildings and work. This photo from Jim Sleeper’s papers at UC Irvine seems to be the oldest mill scene. He dated it around 1900, so it may be Marshal Dunlap’s mill from the 1890s.

Another enduring enthusiast was Henry S. Knapp, a Civil War veteran and former New York office worker who had come to California (perhaps for his health) shortly before the boom. Hearing the glowing reports of the Silverado mines, he came to see for himself and fell hard. He formed the Santa Rosa Mining & Milling Company and set out to lure investors from his old hometown. He found an ally in Brainard Smith, a former reporter for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, who had been keeping bees up in Ladd Canyon. Smith penned a series of lengthy feature stories for the Eagle in 1880-81 which made it sound like the boom was just getting started. Proving, perhaps, that it was indeed easier to get investors from further away (or at least who knew less about mining), Smith’s articles helped Knapp find the money to go to work on the Phoenix Mine, across the canyon from the Blue Light, hiring P.A. Clark as superintendent.

But the deeper they dug, the more problems they faced. Water for one. Not just the lack of it in the creeks to power equipment, but the excess of it in the mines. It flooded adits and collapsed tunnels, adding risk and expense. Some shafts and tunnels had to be abandoned because of the unstoppable flows. The worst incident occurred in September 1881. The Santa Rosa Mining & Milling Company had sunk a shaft some 200 feet down where they struck an underground flow that nearly filled the shaft. To drain the mine, they started a tunnel straight back into the mountain to meet their flooded shaft. Two men – an Irish miner named Josiah Bonney and a Chinese miner whose name went unrecorded – were at work in the tunnel when suddenly the water burst through with such force that Bonney was drowned and the Chinese miner barely survived. The Santa Rosa’s investors shut down operations in 1882, and Henry Knapp’s last fling was managing a group of mines near Hermosillo, Mexico, where he died in 1898.

That left only Marshal Dunlap and his Blue Light Mine plugging along until the end of 1881. By that time, “But two or three men remain at the camp. The post office will soon be discontinued. This would be small hardship, as the office at Carbondale is close by.” (Sacramento Union, 9-23-1881) Two months later, the Union published Silverado’s obituary:

“Silverado is deserted, Cash Harvey holding the fort, solitary and alone. The mines are there yet, however, and the gold-streaked mineral is yet locked in the firm embrace of everlasting hills. The abandonment does not seem to be caused by a disbelief in the value of the mines, for the owners intend to return to their mountain claims where, in the more prosaic pursuit of agriculture in the valleys, they will get together enough lucre to keep them while prosecuting work on shaft, tunnel and winze.” (11-29-1881)

Cassius “Cash” Harvey (1844-1902) hung on for another year and a half, even after P.A. Clark gave up (apparently at the beginning of 1882, when Harvey’s wife, Eugenia, was appointed postmaster). The post office officially closed on January 22, 1883. Harvey packed his family back down to Santa Ana soon after.

Despite the lack of investors (as the old saying goes) time is money, and enough time had now been invested to show that Silverado’s wonderful surface indications were just that. They went neither up, nor down, nor sideways. No one has ever been able to trace the source of those veins, the geology of the Santa Ana Mountains is just too scrambled by earthquake faults. Nineteenth century mining (it is not so different today) was always essentially a form of gambling. And most times, it didn’t pay off.

There is a sense that – at least in retrospect – people wanted to view Silverado as a wild and wooly boom town from the days of ’49. But it wasn’t. Except for a few fist fight and a couple of claim jumping accusations (settled in court, not with six guns), the town seems to have been rather quiet.

The boom was short, but the echoes still lingered.

Working the Blue Light Mine, circa 1930. Longtime superintendent Orville Pember is shown in the center (courtesy the Orange County Archives).

Later Revivals

Over the next 75 years, Silverado went through half a dozen revivals. Not just seeking silver, but gold, zinc, beryllium, and plain old lead.

Once again, Marshal Dunlap helped lead the way. In 1891, after his retirement as Deputy U.S. Marshal, he found the money to start quietly working the Blue Light again. Quiet, that is, until he installed a crusher and concentrator in 1892, connected to the mines by a tramway. “I have always known that it would pay well to work the Blue Light,” Dunlap told a reporter, “but have been hampered by the barrier of no money to push my operations. Now we are on the highroad to success, and I have no doubt but that in a short time talk of the wealth of the Silverado mining district will be heard all over California.” (Mining & Scientific Press, 9-10-1892) He shipped some ore and ran the mine intermittently until at least 1898, and owned the mine until his death in 1904.

In 1903, a group of Long Beach investors formed the Silverado Mining & Milling Company, announced big plans, tried to sell stock, but accomplished little. Two years later the Blue Light was again revived by the Bourland Mine & Milling Co., who put eight or ten men on the job and began shipping ore. But they barely got $75 a ton, and in 1906 sold their lease to what the papers always called a group of French investors (that is, a group backed by the French American Bank of San Francisco). They put a good deal of money into the mine, mill, and new buildings, and started shipping ore to Denver. But not just for silver. Zinc was the new miner’s dream, and the Western Zinc Company at one time claimed to have put half a million dollars into the project. True or not, they were broke by the end of 1907. Western Zinc’s tenure was also marred by two horrible dynamite explosions that left three men dead.

Marshal Dunlap’s estate continued to own the Blue Light, leasing it to optimistic investors now and then, until the property was finally sold around 1919. A new Blue Light Silver Mines Company was formed that year and by 1920 was shipping ore. C. Stanley Chapman, son of C.C. Chapman of Fullerton, the famed oil and citrus millionaire, soon bought a controlling interest in the company. The new company added lead to the list of the mine’s products, and kept after zinc as well, most of which was used in making paint. They ran the mine themselves or leased it to others for nearly half a century, with plenty of shutdowns along the way. All the operators continued to dig deeper and deeper, still seeking that elusive Mother Lode. The last gasp was late in 1968, when silver prices rose and the Miracle Mining & Development Co. of Utah took a five-year lease on the Blue Light. They began preparations to reopen the works, but the devastating floods in January and February of 1969 put an end to the project. The dilapidated old mill buildings were torn down in 1972 and Chapman donated the property to the Cleveland National Forest shortly before his death in 1984.

Today, the old shafts and tunnels are closed, collapsed, or flooded, and all the old buildings are gone. Access to the area is blocked by private property along Silverado Canyon Road (which is vigorously guarded by local residents). Thus the only way to visit Silverado’s mining past is through its history.

If you’re looking for more, here is a collection of original newspaper articles from the boom days.

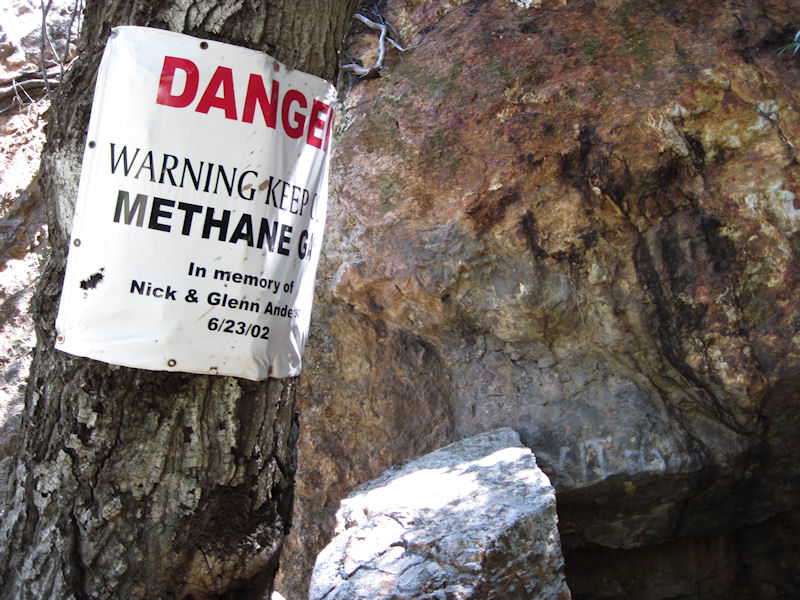

The extreme danger of these old workings was highlighted in 2002 with the deaths of two young men who swam into one of the flooded tunnels and suffocated in the poison gases beyond.