The Portolá Expedition in Orange County

2019 marks the 250th anniversary of the first Spanish overland expedition up the California coast. Unlike the British (and later the Americans), Spanish policy aimed to convert the native population into peaceful, hard-working, Spanish-speaking, Catholic citizens of the empire. In all this, the missions were a primary tool, with only a small military force provided for their protection.

The first explorers traveled north in two divisions – three ships, and two land expeditions marching up through Baja California. Meeting up in San Diego, the exhausted overland travelers found one ship had vanished and the other crews sick with scurvy. But the commander of the expedition, Capt. Gaspar de Portolá, had his orders. He gathered up the healthiest of the men and barely two weeks after his arrival resumed the march north, leaving Father Junípero Serra behind to found the first Alta California mission at San Diego (July 16, 1769). Traveling with Portolá were soldiers from Mexico and Spain, muleteers, servants, and a group of Indian neophytes from the missions of Baja California – about 63 men in all. Their goal was the bay of Monterey.

The men of the Portolá expedition would leave their mark on the history of California in many different ways. Some passed through the story but once. Others played important roles for years to come, serving as Spanish officials, frontier soldiers, and some of the first California rancheros.

Catalonian-born Captain Gaspar de Portolá (1717-1786) was charged with leading Spain’s advance into Alta California. His determination to carry out his orders to plant Spanish settlements at San Diego and Monterey was key to the success of the march north. But his stay in Alta California was brief. In July 1770 he left San Diego and returned to mainland Mexico.

Fr. Juan Crespí (1721-1782), the official diarist of the expedition, served as a missionary in Mexico before coming first to Baja California and then on to the Alta California. He and his fellow Franciscan, Fr. Francisco Gómez, served as chaplains to the Portolá expedition. He spent most of the rest of his missionary career at Mission Carmel.

Lt. Pedro Fages (1730-1796) was commander of the few Catalonian Volunteers healthy enough to make the march north from San Diego. When Portolá left California in 1770 he was appointed military commander, serving until 1774. He returned to California as governor (1782-1791) and during his tenure made the first rancho concessions in Alta California in 1784, including Manuel Nieto’s Rancho Santa Gertrudis, which took in most of Orange County west of the Santa Ana River.

Sgt. José Francisco Ortega (1734-1798), a Baja California military veteran, served as chief scout of the expedition. He was later assigned to assist in the original founding of Mission San Juan Capistrano in October 1775, though it was disrupted a week later when news arrived of an Indian attack on Mission San Diego. He retired in 1795 to his Rancho Nuestra Señora del Refugio, north of Santa Barbara. The Ortega Highway across the Santa Ana Mountains was named in honor in 1929.

(Orange County readers may wonder at the absence of José Antonio Yorba from this list. While long associated with the march of Portolá, modern research reveals that he did not come to California until 1771. He is mentioned in Fr. Serra’s correspondence in 1774 as one of three Catalonian volunteers who had decided to remain in California. “I do all I can to encourage them, in order that, by their diligence at work, and by their economy, they may serve as an example to the others.”)

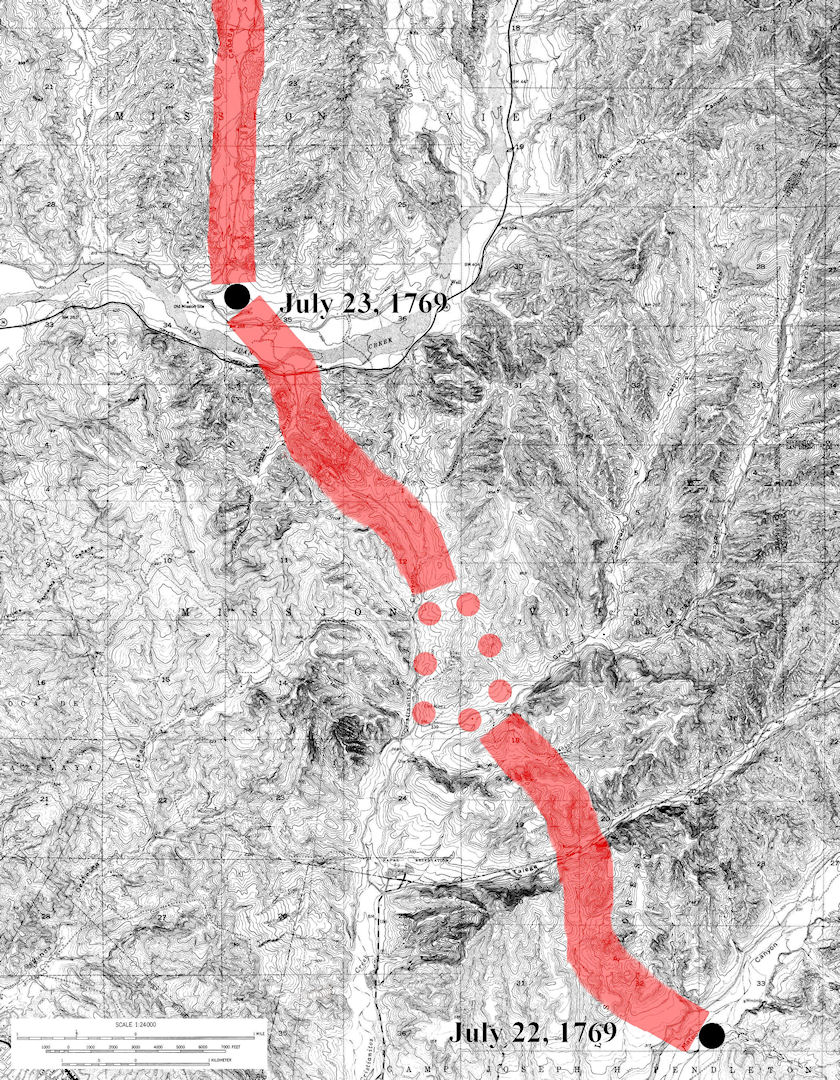

On the trail north from San Diego the expedition advanced slowly, sometimes less than four miles a day, and stopping every four or five days for a rest while the scouts continued to explore the country ahead. Just where Portolá and his men walked and rode across what is now Orange County in 1769 can never be precisely defined. In some places, their route seems clear. In others, we can only guess. Their campsites are fairly well established.

Portolá Campsites in Orange County

July 23, 1769 – San Juan Canyon. Nine days after leaving San Diego, the expedition reached San Juan Canyon, northeast of San Juan Capistrano and made camp at the mouth of Gobernadora Canyon. Here they found a flowing creek lined with trees, grapevines, and wild roses. Fr. Juan Crespí named the spot El Arroyo de la Cañada de Santa María Magdalena, suggesting that it might someday be a good location for a mission.

For many years this little mesa was believed to have been the original site of Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1776, but in the 1960s Orange County historian Don Meadows showed that it was originally founded about two miles downstream and moved to its current location in 1778. Today the “old mission” is remembered in the name of the Rancho Mission Viejo.

July 24-25, 1769 – Arroyo Trabuco. Marching north through Gobernadora and Wagon Wheel canyons, the expedition soon reached the Arroyo Trabuco in Rancho Santa Margarita. Although it was summer, the creek was flowing well and there was an Indian village along its banks known as Alauna. Next to their campsite was Lone Hill. Several of the men climbed it to look out to sea, trying to get their bearings based on the location of San Clemente and Catalina islands.

The expedition rested here an extra day while the scouts explored the area to the north. During their stay here, one of the soldiers lost his gun – in Spanish, his trabuco. So whole Fr. Juan Crespí named the spot San Francisco Solano, the soldiers remembered it as El Trabuco, and it has been known by that name ever since.

This historical marker stands above Portolá Springs Elementary School in Irvine. Tomato Springs was located in the low hills to the right. The expedition camped a short ways west of this little hill.

July 26, 1769 – Tomato Springs. Continuing northwest, the expedition reached the lower edge of the Santa Ana Valley. They expected to make a dry camp that night, but Fr. Francisco Gómez noticed a little green patch in the foothills above which turned out to be two small springs. Fr. Crespí named them the springs of San Pantaleón, but the soldiers called them the Aguage [springs] de Padre Gómez. A century later, they were dubbed Tomato Springs by early American settlers.

Today, a green patched like the one spotted by Fr. Gómez is still visible, but The Irvine Company’s planned community below it is known as Portolá Springs. The expedition camped below on the flats, very near today’s Portolá Springs Elementary School in Irvine.

July 27, 1769 – Santiago Creek. Staying close to the foot of the hills the expedition moved on, passing between Red Hill and Lemon Heights to reach the Santiago Creek in Orange. They made camp on the southern bank of the creek, not far from the Sports Center in today’s Grijalva Park. There were trees and greenery all along the creek, though the water was drying up fast in the summer sun. Fr. Crespí named the spot Santiago, and the name has been in use ever since.

July 28, 1769 – Santa Ana River. After a short march over open, grassy ground the expedition reached the Santa Ana River, near its turn at the mouth of the Santa Ana Canyon (probably about where Glassell Street now crosses in Orange). As before, the local Indians came to visit the expedition’s camp, bringing gifts of food and shell beads. Capt. Portolá gave them beads and cloth in return. To the explorers’ surprise, the Indians also showed them Spanish-style metal tools, which they had traded for – probably from Arizona.

Then suddenly, a strong earthquake struck, followed by two shorter aftershocks, startling both Spaniards and Indians alike. Fr. Crespí named their campsite El Dulcísimo Nombre de Jesús (The Sweetest Name of Jesus), then added del Río de los Temblores (of the River of the Earthquakes). But the soldiers called the river the Río de Santa Ana. Fr. Crespí envisioned a mission here, but instead, Mission San Gabriel was founded further north.

The Portolá Expedition camped somewhere along this stretch of Brea Creek.

July 29, 1769 – Brea Creek. After crossing the Santa Ana River, the expedition marched across the plains, over the East Coyote Hills, and made camp along Brea Creek near another Indian village. The exact site is unclear, but may have been on the north bank where Arovista Elementary School in Brea is now located. As there was little water in the creek, Capt. Portolá gave orders that only the men could drink, and the mules would have to go thirsty.

The next day the expedition marched across the La Habra Valley and crossed the Puente Hills over the little pass where Hacienda Road now runs. In order to cross San Jose Creek the men had to build a crude bridge – in Spanish, a puente – which gave the name to the valley and the hills above.

Little of the Portolá route through Orange County became part of the famed El Camino Real, which tended run along the flats here, where the expedition kept more to the foothills. But a number of the names bestowed both by Fr. Crespí and the soldiers survive. Trabuco Creek marks where one of the soldiers lost his gun – in Spanish, his trabuco. The Santiago Creek was named by Crespí, while the soldiers named the river beyond Santa Ana. La Habra may stem from the pass (abra) where the expedition crossed the hills out of Orange County, and the Puente Hills were named for the bridge (puente) the men built to cross a creek on the other side.

Pushing on slowly north and northwest, the expedition somehow passed their intended goal of Monterey without immediately recognizing it and continued on all the way to San Francisco Bay – at that time still unknown to the Spanish. By then it was November, and illness and rainy weather had begun to take their toll on the men. They turned south, again passing what they now knew had to be Monterey Bay, traveling at two and three times the pace of their slow march north. Supplies were now an issue. All along the way south they ate the weakest of their mules, one by one. They finally reached San Diego on January 24, 1770, having covered some 1,200 miles.

Part of Portolá’s orders were to try to establish peaceful relations with the Indians the men met along the march. In his brief journal he mentions again and again visits from the Indians and distributing gifts of beads and cloth brought along for just that purpose. The expedition seems to have been careful to camp away from village water sources (especially where supplies were scarce), sometimes only taking enough water for the men and not the livestock.

Fr. Crespí mentions that some of the Indians in Orange County began shouting on seeing the Spanish approach but that there was never any show of force, the Indians always approaching them unarmed, making speeches and offering gifts. But sadly, these amiable relations were short-lived. Once the Spanish settled in an area, be it a mission or a presidio, the soldiers often came into conflict with the Indians, much to the frustration of the padres. Yet the story of the Portolá expedition shows that it did not always have to be that way.

Tracing the Trail

Historians have been studying the route of the Portolá Expedition through Orange County for more than a century now. Terry Stephenson, our first great county historian, was collecting material as far back as 1917. Don Meadows began tracing the trail in the 1920s and left us the most thorough account of its route. Beginning in the 1960s, Jim Sleeper studied the route in his role as historian for both The Irvine Company and the Rancho Mission Viejo Company. All of these historians had the advantage of exploring Orange County before it was so heavily developed, but they did not have access to all the diaries from 1769.

As the 250th Anniversary of the Portolá Expedition approached, my friend Eric Plunkett and I decided to take a fresh look at the route, combining original sources from 1769 with modern tools such as Google Earth. Then came the fun part – going out into the field wherever possible to check the diaries against the terrain.

Our results vary only a little from the route suggested by Stephenson, Meadows, and Sleeper. We do not consider it the final word on the subject, and welcome other suggestions. We have plotted it out on topographical maps from the 1940s, when more of the terrain was still visible. The line is purposely wide (the men and mules did not walk in single file, after all), and in two places breaks down into dotted lines where we could not decide between two possible routes. Even after the publication of our book on Portolá in Orange County, we have continued to study other possibilities – especially over the Puente Hills. You can find an expanded, updated version of our research on Eric’s blog, Visions of California.

1. San Mateo Creek to Gobernadora Canyon

2. Gobernadora Canyon to Serrano Creek

3. Serrano Creek to the mouth of Peters Canyon

4. Hicks Canyon to the Santa Ana River

5. Santa Ana River to the Puente Hills

Of course, the men of the expedition saw more than just their line of march. The scouts were out every day exploring ahead, and we know that some of the soldiers also explored a ways up the Santa Ana Canyon while they were camped on the Santa Ana River. We can safely assume that men explored the Trabuco Creek area (when else would a soldier have had the chance to lose his trabuco?). Returning south in January 1770 the expedition went around both the Puente and Coyote hills, staying on the flats to the south, which would have taken them across Buena Park, Fullerton, and Anaheim. And while camped on the Santa Ana River again, on their second trip north in April 1770, the mules and horses were spooked and stampeded off into the night, running at least five miles before they could be rounded up.

Slowly but surely, the Spanish began to learn their way around Orange County, and by the 1790s had probably explored all but the highest mountain peaks.