The Placentia Grass-Eaters

For nearly half a century, a vegetarian, spiritualist, free-love commune in Placentia attracted nation-wide attention for both their eccentric lifestyle and their excellent produce. The Anaheim Gazette once called it “the oddest religious cult ever organized in California” (which is going some).

The Societas Fraternia (as they were sometimes known) were jokingly called the Placentia Grass-Eaters for their strict vegetarian ways. As spiritualists, and “small-c” communists, they stood well within the beliefs of many educated Americans in the late 19th century. All this can be viewed as merely eccentric, misguided, or ridiculous; but there is a darker side to the Grass-Eaters story.

The story begins in 1876 when an English immigrant, George R. Hinde, bought his family to Placentia, built a fine two-story home, and began planting fruit trees. But rumors about the home soon began to swirl – it was painted gaudy colors inside, and the rooms were round! Round, so that unwanted “spirits” had no opportunity to hide in corners. And the fruit trees – as it turned out – were intended to provide the family’s principal diet, for they were strict vegetarians.

George Hinde’s some as it appeared in later years (courtesy the Placentia Library District).

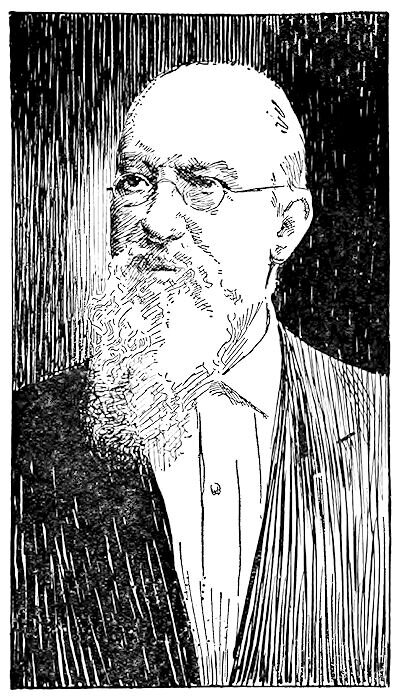

George Hinde (1841-1911) seems to have been a reasonably intelligent, capable individual, and certainly a successful farmer. But he also seems to have been either weak-willed or just plain gullible, and his agricultural success soon attracted others to the ranch.

The first significant arrival was “Dr.” Louis Schlesinger (1832-1906), who arrived in 1878. He was a self-professed medium and clairvoyant who claimed to be in regular contact with the spirit world. His ideas on vegetarianism went far beyond Hinde’s simple views. His insistence that no animal products be consumed – including milk, eggs, and even honey – placed him more on the vegan side; but his demand that none of the fruits or vegetables were ever to be cooked puts him in a whole different category. Nor did he allow any condiments – even salt.

Cooking food, George Hinde later explained, released its “spiritual essences,” and thus it could only nourish the physical being. Their diet, instead, would bring them “into rapport with the angels and ministers of truth which come to earth from the Christ sphere.” Not cooking food also prevented them from canning fruits and vegetables while in season for later use – although they did sun dry a few crops, like raisins.

It was also under Schlesinger’s influence that the ranch was re-organized on a communistic basis, with all property held in common by the members of what he dubbed the Societas Fraternia, “formed for the purpose of teaching by example abstemious[ness] and a higher morality.” Just a few months after his arrival, Hinde placed his property in joint tenancy between himself, Schlesinger, and Ira Carpenter, another wayward spiritualist who invested money in the scheme. He does not seem to have spent much time on the ranch, but his wife lived there for several years.

Schlesinger also seems to have brought in the idea of “free-love” among the members of the community. Again, this was hardly a unique idea at the time (it survives today in the notion of polyamorous relationships), even if “proper” folks always treated it with disgust. In the simplest terms, free-love colonies turned their back on traditional marriage and embraced transient sexual relationships between all persons. “It is perhaps needless to say that they hold the marriage ceremony in contempt,” the Anaheim Gazette noted in 1879, and believed that the sexes should not “co-habitat” except for the purpose of having children.

None of this, of course, made the Societas Fraternia very popular with the neighbors. But what first brought the community to nation-wide attention were charges in 1879 that they were starving their children to death.

The particular case was the Hinde’s youngest son, Frank, who at three months old had been taken off mother’s milk and placed on a diet of fruits and vegetables. Over the coming months (especially as winter made fresh produce less available), he declined, until the neighbors finally felt the need to step in.

The Hindes were arrested and put on trial, along with Schlesinger, who freely admitted they were only following his teachings. Hannah Hindes seemed to view the whole thing in terms of their spiritualist beliefs. “It is no mere whim that has led me to sacrifice (the animal nature merely) of my precious one…,” she wrote to a concerned neighbor. “I have had it all given to me by the messenger of the Most High Ruler of this universe, and I have obeyed their beliefs…. No one will ever know what it has cost me, but I assure you … that instead of ‘losing him,’ as you suppose, I shall rather see him grow up to be a bright and shining light, in a spiritual sense…. I am very sincere and earnest in carrying out the mode of life I now do, and yet I feel truly humble. But I see it will eventually prove one of the greatest blessings mankind ever had.” (Gazette, 5-28-1879) She compared herself to Abraham, being called by God to offer up his son as a sacrifice.

The trial included testimony from various neighbors and most of the doctors in Anaheim, who had examined the child. One described the little boy as “unhealthy, bloodless, and fleshless.” Another stated that anyone who fed a child like that was “criminally insane.”

Schlesinger took charge of the defense, alternating between pleading with the jury and insulting most everyone present. He tried to portray the colonists as persecuted by the Christians and Jews on the jury. The District Attorney, he added, was only in it for the publicity (as was the Anaheim Gazette). As for the doctors, he claimed that if his dietary beliefs were adopted by everyone, there would be no more need for doctors – which obviously tainted their opinions.

Under his questioning, George Hinde testified that he was glad he was a vegetarian. After nine months, he had a clearer mind and better general health. “It was only when the fruits gave out [over the winter] that the child dwindled away.” Now they were feeding him oatmeal, but still no milk – which is unhealthy.

Mrs. Hinde testified that she first resisted Schlesinger’s dietetic notions, but after experiencing the benefits she was converted. “It is the proper diet to develop the highest spiritual being,” she said, adding that the no-cooking rule also freed her from the tyranny of the stove.

Schlesinger addressed the jury directly, stating that since he taught these “dietetic principles,” if any crime had been committed he was the guilty one. What’s more, he said, his teachings would actually benefit society. All great teachers were first met by “slander, ridicule and … libel, persecution and false representation,” he said, citing Galileo, Harvey, Jenner, Stevenson, Morse, and many others. Responding to questions on other matters, he also stated that he was “a free-lover, but not a free-luster.”

In the end, a jury of twelve prominent local men could not agree on a verdict. “It is said that the jury did not believe there was any intent to commit a crime,” the Gazette reported, “and therefore hesitated to convict the defendants. No disposition was manifested to convict Mr. and Mrs. Hinde, as they were so plainly under the control and direction of Schlesinger that they were not responsible for their acts.”

“Dr.” Louis Schlesinger

“It is absolutely painful,” the Gazette editorialized, “to witness the dominion which has been established over the husband and wife by a self-confessed lunatic. We agree with Schlesinger that if any crime has been committed he is the one that should be held responsible. His dupes are so absolutely under this control as to demand immunity for their act…. There is a great deal of sham about ‘Dr.’ Schlesinger and his Societas Fraternia. He never forgets to tell a listener that one of the chief boasts of the Society is to succor the poor. Who have they ever helped?” Many intelligent people believe in spiritualism, the paper pointed out, but the movement is done no favors by “such abominations as the Societas Fraternia.”

The trial prompted a number of newspaper articles, most attacking but a few defending the Grass-Eaters. The Anaheim Gazette was always particularly hostile towards the sect, but was charitable enough to run a few sympathetic articles. One of the more interesting was written by Dr. Eliab Joslin of Orange, who described sharing dinner with the residents. He praised it as a healthful regimen, and noted that – in late summer 1879 – “even that little baby is now a healthy, bright and beautiful child.”

Yet within a year, Louis Schlesinger had abandoned the sect, reportedly taking with him everything of value he could carry – cash, jewelry, clothes – and George Hinde was forced to declare bankruptcy and lost part of his property. “Everybody breathed a sigh of relief when he was gone,” one Placentia pioneer recalled.

“Professor” Schlesinger continued to confound the gullible as a traveling performer. His favorite trick involved identifying names written on slips of paper – a trick recognizable to many magicians. Despite his claims of great spiritual power, he was not infallible, and it sometimes took him two or three tries to achieve the desired result – if at all. He was both celebrated and ridiculed by turns for the rest of his life.

George Hinde struggled to restore his family’s fortunes, winning prizes (and customers) for his produce. Selling fruits and vegetables was the major source of income for the sect over the years – though curiously, they dabbled in financial investments as well.

With Schlesinger gone, the residents had also gone back to cooking some of their vegetables. In 1882, Hinde told the Anaheim Gazette that after almost four years of raw produce, they “enjoyed perfect health,” still eating those things that could be eaten raw, but now cooked things like beans, peas, and potatoes. “Our object in making this change is to ascertain chiefly whether the theories advanced hitherto have any basis in fact; we also deem it best to use your columns to enlighten the public, rather than allow them to be duped by idle and ridiculous stories about us as it has been in the past.”

(The Gazette also reported with glee that Schlesinger had gone back to eating meat – and was said to have gained 40 pounds!)

But as their plantings flourished, death began to stalk the Hinde family. Three of his children died as teenagers in the early 1880s. Son Harry died in 1881 after infection set in after a fall. Daughter Alice died in 1885. “As Faithists,” her family announced, “we entrust her to Him who gave, and has called her to higher duties.” In publishing their statement, the Anaheim Gazette (6-20-1885) added, “Their religious belief is, or was spiritualism; they now call themselves Faithists, a term the meaning of which is a mystery to all but themselves…. [O]ne of the beliefs of the Faithists is that whatever is, is right, and that the ministrations of a physician cannot avert the decree of inevitable fate.” Not avert it, perhaps; but the coroner’s jury felt Alice would have lived longer with proper food and medical care.

At his baby brother’s trial in 1879, 13-year-old Alfred Hinde had testified that he appreciated his new, uncooked, vegetarian diet, and wouldn’t go back if he could. By1885, he was also dead. Hinde’s wife, Hannah, died a slow, agonizing death in 1886. Dr. Joslin attended her in her final illness.

This string of deaths also marks the beginning of another custom that cast suspicion against the Grass-Eaters. Most (if not all) of their dead were buried right there on the ranch. This was not unheard of at the time, and county records often note these private interments. But after the starvation trial, the secrecy bred suspicion. Who else might be being buried beneath the fruit trees? How many other children were being starved?

The whole situation made the Grass-Eaters an easy target for sensationalist reporters. This 1886 feature from the Los Angeles Herald is about as scathing as anything ever written about them:

THE STARVATIONISTS.

Slow but Sure Homicide – A Crime Against Humanity.

“The Herald last year called attention to the starvation of a young woman at the insane and idiotic establishment in North Anaheim, known as the vegetarians, or persons who ate no meat of any kind or cooked food of any sort.

“This establishment was started by an Englishman named Geo. Hinde about eight years ago, with property held in common, and all food used to be uniformly vegetable, in order to avoid the grossness and sensuality that was supposed to be derived from cooked food, or what they termed dead food. Meat they denominated a corpse which would be a pollution to eat. By eating only fruits, vegetables and grain in their raw state they claimed that they partook of the pure life of plants, that would be killed by cooking, and would receive into themselves all of the spirit life of these products till they would become spiritually minded and hold converse with the spirit world, free from all the passions and ambitions which prevail in our common humanity. In other words, they would reconstruct the style of living and go back to the life of the deer and the bison.

“The experiment has been tried long and earnestly with most foolish and fanatical zeal. One after another has left the society by resignation or starvation until only a few are left hanging on the verge of death….

“It is to be hoped that this diabolical heresy against humanity, against reason and revelation, against the structure of the bones and sinews of the frame and the composition of the blood that pulsates through every throbbing heart, will here find an end and a death that has no resurrection. It has been a damaging delusion, without an apology, without precedent, without knowledge of physiological science and contrary to the accumulated wisdom of the human race.

“It is fitting that the end should be unobstructed death, that they should die as an example of their folly; but henceforth when any more of these insane societies are formed the insane asylum should be the speedy home of their founders.”

*

Sadly, in 1883, another charismatic, strong-willed spiritualist arrived, and like Schlesinger, pushed the family in new, unorthodox directions.

Walter Lockwood (1851-1921) was born in England of Jewish parents, and had been a minister in the Primitive Methodist Church before being converted to spiritualism. Along the way he acquired a new surname – Thales, in honor of the early Greek philosopher/mathematician. In America, Lockwood/Thales seems to have been looking for a spiritualist community to lead. How he became aware of the Societas Fraternia is unclear, but he eventually made his way to Placentia.

Thales even came equipped with his own “bible” to guide the community – Oahspe: A New Bible, which had been published in 1882 by a New York dentist-turned-prophet. Thales, in fact, had served as one of the editors of the 900-page book which purports to trace 75,000 years of cosmic history. Besides promoting its own unique views, the book also makes libelous assertions about the origins of Christianity, and for good measure also attacked the republican form of government. Orange County historian Jim Sleeper once described it as “a strange conglomeration of spirits, spookery and ancient history.” The Philadelphia Times judged it a “crank’s collection of all the cranks have been saying for thousands of years; as full of darkness as it is of conceit.” Converts to the Oahspe’s teachings called themselves Faithists, and formed their only colonies in New Mexico and then Texas. Thales added these tales to the teachings of the Placentia Grass-Eaters.

“As Faithists,” said Thales, “we are all brothers and sister. When it appears to be the will of the Great Spirit that we should increase the number of our colony, the pair that are chosen are instructed by the spirit guide. They assume the marriage state for a short time, and after the production of offspring return to the state of brotherhood and sisterhood.”

But Placentia’s Faithist colony never grew to any great extent. Counting wives and children, Jim Sleeper estimated there were only about 30 members over the years. At one time or another they planted most anything that will grow in Southern California – oranges, peaches, grapes, watermelons, apples, tomatoes, bananas, figs, chestnuts, corn, beans, peas, strawberries, walnuts, olives, loquats, avocados, macadamia nuts, and more.

Not content with merely growing produce, the colonists also experimented with new varieties, developing several successful hybrids, including the Placentia Perfection Walnut, Thales Persimmons, and Thales Loquats. (While Thales may have put his name on them, George Hinde actually developed these new varieties, along with several new strains of avocados.)

William and Matilda Wiederhold, circa 1885 (Jim Sleeper papers, UC Irvine Special Collections).

The next important addition to the colony came in 1887 when German-born William Wiederhold (1845-1922), his wife, Matilda, and their two sons, Ross and William, arrived. Another son was born on the ranch and later buried there. The Wiederholds would play a key role in events on the ranch in the coming decades.

The Grass-Eaters made national news once again in 1890, when they refused to answer questions for the Federal Census. (This was Thales’ doing, as the members had dutifully answered questions a decade before.) The coverage was not as lurid as the starvation trial, but Walter Thales certainly made for good copy. When asked why they would not answer census questions he explained that it was because they were not citizens of the United States but citizens of the world. “We recognize the right of no one to make laws for us except the great Jehovah.” “We do not recognize the right of any king, emperor, priest or leader to rule over us. Each man governs himself through the dictates of his own conscience.”

Asked by a reporter for an explanation of the principles of his faith, Thales said it was contrary to their principles to give out such information. “What would it profit [you] to know our principles? They do no concern you. We are merely making experiments in matters of diet and life. As soon as these experiments have reached a state from which we can draw conclusions, you and the world shall be given the benefit of our experience.”

He said the sect was not looking for converts, but did accept some of those who came seeking. He denied that they “do not respect the sanctity of the marriage tie and … advocate free love.” “Whoever says that lies. We are pure, lead pure lives and are learning lessons of purity. By our lives and our faith we are trying to show what a pure life, led and followed by pure motives, would result in.”

But the “world” still insisted on enforcing its laws, and Thales, Hinde, and Wiederhold were fined $50 each for their refusal. In the coming years they answered the census taker’s questions – with Thales always listed first.

After an interview, a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle (6-20-1890) added that Thales’ “phrenological development shows that his mental and moral faculties are deficient, while his animal faculties are largely developed. It is perhaps well that such men as he should live on a vegetable diet.”

Phrenology (jokingly called, ‘reading the bumps on one’s head’) was another bit of 19th century pseudo-science that claimed to be able to identify a person’s characteristics from the shape of their skull. Though long since discredited, the reporter’s conclusions (whatever his methods) seem fairly accurate. There are good indications that Thales was what we would now call a sexual predator, and that his targets were usually the young girls living on the ranch.

That number increased in 1890, when Mrs. Ida Smith brought her two daughters to the ranch. Thales had decided that the children should no longer attend public school, and Mrs. Smith was brought in as a private tutor. She was also a practical nurse. This decision may have been made after two of the boys, Frank Hinde and Ross Wiederhold, decided they’d had enough and tried to run away. They said they were tired of living on turnips and carrots. They got as far as Los Angeles, but were quickly returned to their parents. They got a good meal before they were taken home, but expected “a sound thrashing” after that.

26-year-old Lilly Hinde, one of George Hinde’s two surviving daughters, took another way out. In 1899 she drowned herself in a nearby reservoir. “I am suffering so much from ill health life is not worth living. I hope you will forgive me, father,” read the note she left on the bank. The Anaheim Gazette reported that she had been “cohabitating” with Thales (8-24-1899). “She had suffered for some time from melancholy, induced by illness,” the Santa Ana Blade added. A later account claimed she had killed herself on account of Thales’ “persistent attentions.”

Ross Wiederhold ran away for good in the late ‘90s. He returned in 1901 to try to lure one of his younger brothers to join him. When Ross was not seen for a few days, this led to new rumors that he was being held against his will. Sheriff Theo Lacy was finally sent out and allowed to search the premises. A curious reporter from the Santa Ana Blade accompanied him.

“[T]he terrible ‘grass eaters’ and torturers of innocent children and women,” he wrote sarcastically, “alleged red-handed murderers, and inhuman monsters, were all there … three of them, all looking as though they had just stepped out of some old painting, not the pictures of pirates and buccaneers, but rather from some pastoral scene, for they were the most inoffensive, patriarchal looking old chaps possible to imagine…. [T]he people are vegetarians, it’s true, and neither butter, meat, eggs nor fish are used as food by them, but they have an abundant supply of flour, canned and preserved fruits of almost every description, honey, olive oil, walnut oil, and coconut butter and vegetables of all varieties grown in Southern California….

“The house … is plainly but comfortably furnished and contains a bathroom and all modern improvements…. These people are spiritualists, and their at all times peculiar religious beliefs are said to have been frequently subjected to change, and it is openly admitted by them that their ideas on marriage are in direct opposition to those generally accepted by the majority of civilized people, but if appearances count for anything, they are inoffensive and industrious people and mind their own business with a continuousity [sic] and vehemence of purpose that might well be emulated by more aspiring members of society.”

It turned out Ross Wiederhold’s brother had died the year before (his death certificate and burial permit were on file with the county, the Blade pointed out). Ross, the men said, had been allowed to visit, “but he had been driven away again as his father and L.W. Thales claimed he had stolen from them and they would not allow him to come back to remain with them.” But still, they allowed Lacy to search the premises from “attic to cellar.” (Blade, 5-23-1901)

Ida Smith seems to have died sometime before 1900, but her teenage daughters remained on the ranch. In 1905, George Hinde again placed the property in joint tenancy between himself, his son Frank, Walter Thales, and William Wiederhold – each with the right of survivorship. It was a decision that would lead to a host of lawsuits in later years.

George Hinde died in 1911, at age 70. His last surviving daughter, Cora, followed him less than a year later, leaving Frank Hinde, Thales, and Wiederhold to run the ranch.

The colony finally began to crumble in 1921-22, with the deaths of Walter Thales and William Wiederhold just two months apart, sinking into a flood of lawsuits over who would inherit the valuable ranch. Thales’ will left the property to Wiederhold, but Mrs. Wiederhold filed suit, declaring that he was incapable of managing the $60,000 estate. Thales’ (which is to say, Lockwoods’) siblings in England also entered the fray, claiming a share of both property and cash.

The resulting trials allowed the newspapers to once again publish lurid tales of life on the ranch. Thales, the “self-asserted companion of spirits who dwelt in his brain and sat on his lap,” was said to have “declared that he was directed by spirits to supervise the mating of colonists or followers of the cult.” This, along with their raw food, vegetarian diet, “undermined the physical and mental health of the colony. An incurable disease was introduced it was alleged [identified in court documents as syphilis]. Many children died of malnutrition, many other committed suicide and many were invalids…. Thales himself it is charged was made weak in mind and body.” Their dead were buried under “a certain fruit tree, under the theory that the spirit would enter the tree and influence its productivity.”

“Few members of the cult remain,” the Santa Ana Register (4-22-1923) added. “Those who do, however, hold to their former customs and hold their premises inviolate to intrusion from non-believers…. Spiritualism and vegetarianism were among the practices followed by the cult, besides those of avoiding speech or handshakes with those outside the circle of belief.”

“Neighbors say that Thales died a horrible death. With the members of his colony gathered around his death-bed the leader cried out that the good spirits which never before had left him had forsaken him as he was about to die. Beating his breast he died in a fury.”

Matilda Wiederhold consented to a few interviews. “Mr. Thales was a great man,” she told a Register reporter (10-31-1922), “And, being great, he was misunderstood. Yet, no one could confound him – not even the lawyers.”

After all the recent legal battles, Wiederhold, “a thin little woman of 64,” had no sympathy for lawyers – and even less for reporters. The lawyers lied about what she called the Placentia Vegetarians colony. She was still defensive about old time rumors about the residents: “There never was the slightest suggestion of ‘free-love’ here. Free religion – yes, of course; but no free-love. You believe in free religion? You ought to believe in it. This is a free country, is it not?” Pure thinking is the essence of pure living, she added.

Syphilis, she claimed, “was long ago eradicated” among the colonists through celibacy. “Mrs. Wiederhold emphatically resents every inference that other than a very few members of the colony suffered from the disease or died from it.”

“Our friends,” she said, “and there are many of them, know better than to believe those other fairy stories, but if the rabble will believe such rubbish, they are welcome to it.”

The recent burials of Thales and her husband were still in evidence when reporters visited the ranch, the graves beneath the trees marked by simple palm fronds. Their bodies, Mrs. Wiederhold explained, were of no further use to them, once their spirts were “freed from its cumbersome burden … [and] soared to nobler realms,” so they were returned to the earth.

In the end, the Public Administrator was left to sort out the details, and the property continued in joint tenancy. Soon after, Matilda Wiederhold and her son, William left the ranch.

To fill the gap, Hinde made a deal with neighbors Miles and Lida McCarty to join him in running the ranch. The final addition to the ranch residents came in 1923, when Vera Smith (at just 33 already prematurely gray) married Asa Foust.

The McCartys attempted to introduce Hinde and the Smith sisters to orthodox Christianity, and at least one newspaper article claims the girls were converted. But the Grass-Eaters really passed away with the death of Frank Hinde in January 1924. Though some neighbors remembered him as disabled (perhaps from an accident?), he was still as successful a farmer as his father. Born on the ranch, “he will be laid on a wooden bier, wrapped in sack cloth and lowered into a grave on the estate.” It was the trial over Hinde’s health, 45 years before, which had first brought the colony national notoriety.

“The Smith girls and poor Frank Hinde had good minds,” Mrs. McCarty later told a reporter, “and, aside from their curious bringing up, were honest people. Frank Hinde died a few months ago. I nursed him during his last illness. He was just like a child up to the last.”

The McCartys finally ended up with the ranch, trading for the Wiederhold share and inheriting Frank Hinde’s interest. In 1931 they sold the ten-acre parcel to wealthy Placentia rancher S. James Tuffree. At the time, there were six acres of persimmons (which Tuffree pulled out and planted to Valencia oranges), two acres of avocados, and an acre of guavas, “the balance being in walnuts, nursery stock and semi-tropical fruits.” Tuffree soon tore down the famous old round-roomed house and built a modern home in its place. The story of the Placentia Grass-Eaters passed into history – or rather, myth, as tales continued to be told.

*

In the 1980s, Orange County historian Jim Sleeper did extensive research into the history of the sect, planning to tell their story in the form of a historical novel. He asked several old Placentians about their memories of the Grass-Eaters. Thales was recalled as tall and thin with a long beard, and described as bright, educated, good-looking, and well-spoken. Matilda Wiederhold was described as rather the “queen bee” of the place, who did most of the talking when people visited the ranch – unless Thales came around; then everyone would clam up. Her son, William (always called Willie) was amiable, but always seemed shy around strangers. Others remembered the children “looked forlorn, like caged animals.” Rumors of other children born on the ranch continued to float around – all of them buried under the trees.

People hated them, the old timers said, but they would still come around to buy their excellent produce and nursery stock – and even bread (the ban on cooking long since forgotten). It was sad, really, one old timer told Sleeper.

George Key (1896-1989), whose family ranch has been preserved as a county historical park, always doubted the more lurid tales of the Grass-Eaters. “The people as I remember,” he told Sleeper, “lived pretty much to themselves. However, I can only remember them as friendly, generous and cordial. The young people always seemed a little reserved or withdrawn, but friendly…. I know many people rather looked down on the colony and some unkind things were said. I believe it was largely because Placentia was rather conservative in many ways and did not believe people with beliefs like those that were reported had a place here.”

The Key family, at least, seemed to treat the sect’s spiritualist views as something of a joke. Key often told the story of how after his father’s death in 1916, Matilda and Willie Wiederhold came to pay a condolence call on his mother. Mrs. Wiederhold said, “If you ever want to send a message to your husband, just let me know, because his spirit is resting on our mantle.”

Mrs. Key, newly widowed, looked at her with a twinkle in her eye and replied, “We have four mantles in our home. I believe if he was going to be on anybody’s mantle he would come home to roost.”

But as tales of illness, disease, despair, and death continued to pile up, Sleeper finally abandoned his novel. The story had become just too gruesome.

In his surviving notes, Sleeper analyzed the community’s fear and hatred of the Grass-Eaters. The neighbors, he wrote, felt threatened by them and their ideas. Their unorthodox religious beliefs, unique dietary restrictions, and their communal way of living all marked them as outsiders. And as they cut themselves off from society more and more – not sending their children to school, resisting governmental interference – it only made them seem more suspicious. And so the tales grew.

But many of them are true.

George Hinde’s original, simple, vegetarian views were harmless enough; but when it became part of his religion, it grew into a tyranny, adding more and more increasingly unorthodox ideals to his daily diet.

“When Mr. Hinde began his self-imposed task of reforming the world,” the Anaheim Gazette noted in 1885, “– or that part of it which was in his reach – there were not wanting other reformers who desired to share with him the comforts of his beautiful home and the work of reformation.” This included “the notorious Dr. Schlesinger,” and Ira Carpenter, “an enthusiast who found the world too vile to mix with, and who desired to retire therefrom and dream away his life among those who could appreciate the high and pure aspirations which he fulminated. His plausible manner won the confidence of the Hinde family,” and by offering to help pay some of their debts, he got them to agree to transfer the property to a new association – Schlesinger’s Societas Fraternia. Since then, Hinde had “grown less credulous and more suspicious of the motives of the reformers that quite often sought to intrude their presence into his home.”

Yet that did not keep out Walter Lockwood Thales, and his “Faithist” religion. Before long he came to dominate the family “in every way possible,” as one Placentia old timer put it. “No one could say that he had not been lord and master of this colony…,” the Register noted after his death. “Without his permission none dared to speak. He conducted so called religious services, some have described them as more like trances, and guided the members of his religious family in daily toil in the orchards and fields with propitious results. Under Thales dictation, the grown men and women acted like children, old timers at Placentia say.”

Was Hinde really so weak-willed that he could be so easily dominated by these admittedly powerful personalities? Or was he a searcher, seeking something he could not find? Or perhaps he had simply fallen into the trap of seeking novelty for novelty’s sake; of embracing an idea not because of what it is, but because of what it isn’t, eschewing anything embraced by the masses?

Whatever you think about religious cults, spiritualism, vegetarianism, or even free love – they turned out to be a deadly combination for the Placentia Grass-Eaters.