The Anaheim Gazette and its Publishers, 1870-1964

The Anaheim Gazette was first newspaper published in what is now Orange County, California, and played an important role in the development of the county. For decades, it served as an important source of information, advertising, editorials, and community connections. Today, its pages provide a unique glimpse of the people, places, institutions, and events which make up the early history of Orange County.

In 1870, Anaheim was the largest community in southern Los Angeles County. Two years before, the old Mexican ranchos surrounding the townsite had been broken up for sale as farms and homes, prompting a surge of growth that included the founding of several nearby towns and the incorporation of the City of Anaheim in February 1870. That summer, local merchants offered a subsidy to anyone who would launch a newspaper in the growing city.

George Washington Barter, co-owner of the Los Angeles Star, took up the offer and in late September issued a prospectus for the new paper, hoping to begin publication in just three weeks. An old flatbed printing press was secured, but it took a little longer to find a competent printer and typesetter and the first issue of the Gazette is dated October 29, 1870.

These were the days of openly partisan newspapers, but while Barter himself was Democrat, he announced his paper as an independent sheet – a safer policy in a one-paper town. One of the Gazette’s first editorial campaigns was for the creation of a separate Orange County, carved out of the southern end of Los Angeles County. It also documented the development of such surrounding communities as Santa Ana, Westminster, Tustin, and Orange, eventually securing local correspondents in each town.

Barter’s financial support may have only been promised for the first year. In any case, he sold the Gazette in October of 1871 and returned to the Los Angeles Star. He published it for about a year and a half, but, as Los Angeles historian James M. Guinn wryly noted, “that was long enough to take all the twinkle out of it.”

Barter had been trained as an attorney before becoming a newspaperman. Anaheim historian Leo J. Friis described him as “better than average” as an editor, while, “as a Beau Brummell and philanderer he was unsurpassed.” He was noted for his style, and his fondness for the ladies, so Los Angeles was shocked early in 1873 when his wife and young daughters showed up in town! A messy divorce followed and Barter skipped town, leaving behind his ex-wife, his daughters, and his debts. He continued in newspaper work elsewhere for several years and died in a Seattle asylum in 1891.

The second owner of the Anaheim Gazette was Charles A. Gardner. Hoping to increase the paper’s status and circulation, in December 1871 he renamed it the Southern Californian. But publishing a weekly newspaper may have proved more work than Gardner expected, and in December 1872 he sold the paper to Anaheim saloonkeeper Richard Melrose, who hired George C. Knox as editor. “Anaheim has always accorded a liberal patronage to its newspaper,” the Los Angeles Star (Dec. 9, 1872) reported, “the receipts of which have, since its inception, generally exceeded $500 per month.” All this with a reported circulation (in July 1873) of just 300.

But advertising and subscriptions were not the only source of income for a small town weekly. “Job printing” also added to the monthly receipts, with outside printing orders ranging from business cards and stationery to pamphlets and even small books. As publisher of the Gazette, Richard Melrose could lay claim to the first book published in Orange County (1874), and the first promotional pamphlet on the area, Anaheim, The Garden Spot of Southern California (1879).

George Knox soon bowed out of the Gazette, and in 1875 Richard Melrose took on a new partner, Fred Athearn. Together they made two attempts to increase the Gazette from a weekly to a daily paper (August 1875–July 1876, and January–December 1877). The weekly Gazette continued to be published during those months for circulation in the outlying communities.

In January 1878 Melrose & Athearn tried again, this time launching a semi-weekly edition published twice a week. But in July 1878 the partners announced that the Anaheim Gazette was up for sale. Just a few weeks later, when there was no immediate buyer, the two decided to dissolve their partnership, with Richard Melrose continuing on as sole publisher of the weekly and semi-weekly Gazette. The semi-weekly was abandoned in August 1879. Fred Athearn died of tuberculosis in 1881.

During the early 1870s, Richard Melrose had been studying law, and in 1877 he was admitted to the California bar. In the 1880s, he served as Anaheim’s City Attorney, as well as Postmaster (1884-85). He also began investing in Southern California real estate. When the big real estate “boom” of the late 1880s hit he jumped in with both feet, investing (among other things) in Anaheim’s first streetcar line, and the elegant Hotel del Campo. In October 1887, when the boom was near its peak, he sold the Gazette to Henry and Charles Kuchel, his brothers-in-law.

But booms never last (or else we wouldn’t call them booms), and in less than two years the “boom of the eighties” had run its course. Like many investors, Melrose struggled for the next few years but eventually recovered, re-establishing himself as a major figure in the community. His legal career was especially noted for his work on water rights; his political career peaked in 1909-10 when he served a term as Orange County’s State Assemblyman; and his real estate investments eventually paid off. In 1910, Albert Bradford laid out downtown Placentia on Melrose’s property; while in Los Angeles, Melrose Avenue marks another of his investments. He died in 1924, at age 74.

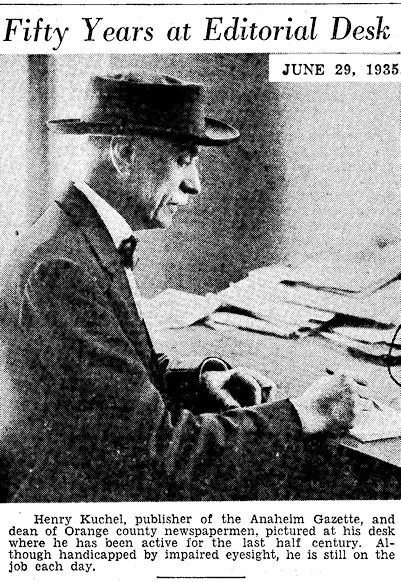

The new owners of the Anaheim Gazette, Henry and Charles Kuchel (pronounced Keek-ul by the family) were sons of one of the founders of Anaheim and had grown up there. Henry, in fact, had worked for George Barter as a printer’s devil and newsboy when the Gazette was founded 17 years before. From there he went on to work for other papers up and down the state before returning to Anaheim to run the Gazette. In May 1899 he bought out his brother, and continued to publish the Gazette until his death. Charles Kuchel (1866-1946) went on to serve as Anaheim’s Justice of the Peace for more than two decades (1924-46).

Henry Kuchel was a man of strong opinions, well suited to the personality-driven journalism of the day. Famed Santa Ana editor Dan Baker considered him “an elegant and forceful writer.” His editorials reflect his distinctive views, and earned him praise from his supporters and attacks (sometimes even physical) from his opponents. But through it all, he was a constant booster for his hometown. He is sometimes said to have coined the nickname “The Mother Colony” for Anaheim.

His first big political battle came just two years after buying the Gazette, when the 20-year drive to create Orange County finally came to a head. But while the Gazette had supported the idea since its founding, Anaheim now found itself playing second fiddle to Santa Ana. Kuchel cried foul when the upper boundary of the county was moved south from the Rio Hondo to Coyote Creek, leaving Anaheim near the northern end of the new county, and always complained bitterly about the city’s betrayal. But the fact that Santa Ana – not Anaheim – was clearly going to become the county seat probably had as much to do with his attitude as anything.

So this time the Anaheim Gazette led the battle against the creation of Orange County, publishing numerous articles, letters, editorials, and even a pamphlet of Reasons Against County Division. “If Santa Ana desires division so passionately let her draw the dividing line to the south of us,” Kuchel wrote (Jan. 17, 1889). “We assert that the act creating the county of Orange is drawn simply for the aggrandizement of a few people at Santa Ana.” (Jan. 31, 1889). But the voters disagreed, approving the new county by an overwhelming majority in June 1889. It was one of Henry Kuchel’s few political defeats.

Kuchel’s biggest challenge, though, came around 1905, when a household accident left him almost completely blind. But he refused to let his disability slow him down. He continued as publisher of the Gazette, keeping up with the news by having several papers read to him each day (when radio news came along in the 1920s he considered it a great gift). He continued his editorial writing, dictating them to his wife, Lutetia (1870-1968). His older son, Ted (1900-1984), joined him in the management of the paper in the 1920s. It was during this time that the Gazette joined all but one of Anaheim’s papers in fighting the Ku Klux Klan’s efforts to take control of the city government.

Kuchel’s younger son, Tom (1910-1994), became an attorney, later serving in the State Assembly (1937-40), the State Senate (1941-46), and as a United States Senator (1953-69). He was considered a liberal Republican, and supported much of the civil rights legislation of the 1960s.

Henry Kuchel died in August 1935, at age 76. At the time, the Gazette was the second oldest weekly paper in Southern California. In 1960, he was elected to the California Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Ted Kuchel followed his father as publisher and the family continued to publish the Gazette for another quarter of a century. In the early 1950s, the Anaheim Gazette became a daily paper again. But increasing competition (especially from Anaheim’s longtime daily paper, the Bulletin) soon forced it back to a weekly. In October 1961 the Gazette was finally sold to Virgil Pinkley, who owned a chain of local newspapers around Southern California. In 1965, “Lute” Kuchel and her sons presented the priceless original files of the Anaheim Gazette to the library of the new University of California, Irvine.

Virgil Pinkley published the Anaheim Gazette for less than three years. He built a new plant where he printed several of his local newspapers, including the Orange Daily News. He also shared staff and content between his various papers.

But by then, Orange County journalism was dominated by the Santa Ana Register. Through their parent company, Freedom Newspapers, they were slowly buying up their competition, and shutting down local papers left and right. In August 1964, Pinkley sold both the Gazette and the Daily News to Freedom. By then, Freedom Newspapers already owned the Anaheim Bulletin (along with the La Habra Star and the Brea Progress), so it didn’t take long for Freedom to shut down the weekly Gazette in favor of the daily Bulletin.

After ninety-four years, on November 25, 1964, the Anaheim Gazette published its last issue. The Bulletin survived until 1992, when it was reduced to a weekly community insert.

For nearly a century, the Anaheim Gazette and its publishers played an import role in the growth, politics, business, and history of Anaheim. From the days of hand-set type and personal journalism to the days of newspaper chains and corporate ownership, the Gazette helped to build community and crystalize local opinion. Today, it serves as an invaluable historical resource for anyone interested in our rich past.