The Town of San Juan Capistrano

San Juan Capistrano has been an Indian village, a Spanish mission, a Mexican pueblo, and an American city. But there’s another link in that chain that’s often been overlooked – and it turns out to be quite a story.

To set the stage, we need to go back to the 1840s. In 1841, the little community that had grown up around Mission San Juan Capistrano was declared a pueblo (town) by the Mexican government. Five years later, Emigdio Vejar, the local juez de paz (justice of the peace), was granted the Rancho Boca de la Playa, between the pueblo and the sea.

Skip ahead two decades. California has passed from Mexican to American control, and Congress has required that all landowners submit their claims for review. It was a complex, lengthy process, where landowners were required to prove their claim rather than the government have to prove it fraudulent, and it dragged on for decades. Capistrano’s pueblo status had been lost through failure to submit a claim, the Catholic Church had proven their rights to the mission buildings and a few surrounding fields, but the exact status of the Rancho Boca de la Playa was still up in the air.

The grant itself had been found valid by the American courts; the question now was, just where were its boundaries? All the government had to go on was a brief written description (“bounded on the north by the ciénega … on the south by the beach, on the west by the first hills of the Cañada of the Boca de la Playa”), a crude map (diseño), and the word of its owner – at that time, Pablo Pryor, the son of an American trapper and a Mexican paisana, Teresa Sepúlveda, who had acquired the rancho in 1860.

And that’s where the trouble started.

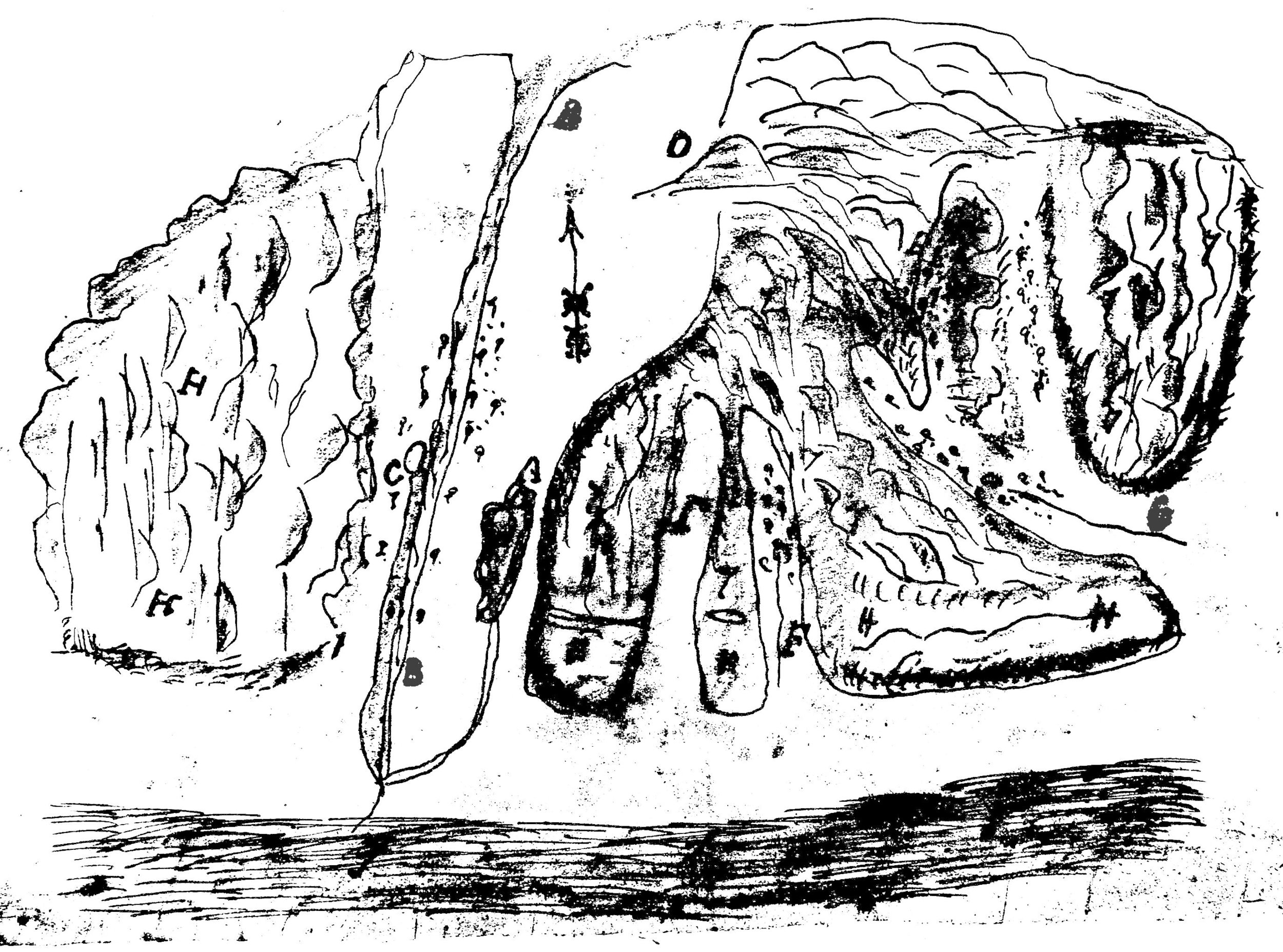

The diseño for the Rancho Boca de la Playa, circa 1846. The main watercourse (B) through the center is San Juan Creek as it drains to the sea. C is a spring (aguaje) To the right are the Cañada de los Desechas (F) and the Cañada de los Pulgas (G) – not the “Canyon of the Fleas” further down the coast, but presumably Segunda Desecha Canyon in San Clemente (courtesy the California State Archives).

Pablo Pryor seized on the uncertainty to try to “float” the boundaries of his rancho north. What if that “ciénega” (marsh) was actually up near where Trabuco Creek joined Oso Creek? That would give him a lot more land. The problem was it would also take in the entire community of San Juan Capistrano!

Pryor managed to find a few allies willing to support him in his claim, and a surveyor to run the lines. In 1869 Max Strobel drew a map of the Boca de la Playa that included all of San Juan Capistrano, “and the claims of over a hundred persons.” (Los Angeles Star, 7-8-1870)

Father Joseph Mut, pastor at Mission San Juan Capistrano, 1866-1886.

When they learned of this fraud, the people of Capistrano naturally protested. Leading the opposition were an unlikely pair – storekeeper Henry Charles (a Russian Jew), and Fr. Joseph Mut, the Spanish-born priest at the mission. Charles had a stake in all this as he owned plenty of land around the valley, but for Fr. Mut, the offense ran deeper.

“The old Paisano settlers still gratefully remember Father Mut’s sacrifices in their behalf,” Father Zephyrin Engelhardt noted in his 1922 history of the mission. “Father Mut was the lawyer (el abogado) of the poor,” longtime resident José Juan Olivares recalled in 1925. “That way the rich didn’t like him…. Father Mut used to say ‘It is easier for a camel to go through a needle’s eye than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God.’ He used to rail at [the] rich for their treatment of the poor.”

“On appeal from poor Californians and Mexicans,” Fr. Engelhardt wrote, “Father Mut by his counsel and otherwise, endeavored to save the little property they had always regarded as their own. He even at great expense sent an agent to San Francisco in order the thwart the machinations of landsharks.”

That agent would seem to have been Henry Charles, who wrote to “the vigilant pastor” from San Francisco in September of 1869:

“We went [to the Surveyor General’s] and examined what the other party had been doing, and what do you think we found? We found the Affidavits of N.N.* swearing that there is a cienega at the corner stones of Boca de la Playa on the road above the place of Rosenbaum. I saw the Affidavit myself, and will bring copies of them with me.”

[*In quoting this letter, Fr. Engelhardt, “in mercy,” deleted the names of “two paisanos and two who were not paisanos” who were involved in the “scheme of gobbling up lands belonging to the Mission itself.”]

“Once Father Mut found it necessary to make the tedious and expensive journey to San Francisco himself,” Fr. Engelhardt added, “and he appears to have been successful.” The Strobel map was rejected by the government in 1870.

But there was a price to be paid. “The kindhearted pastor incurred the bitter animosity of real estate men and lawyers who seem to have been indifferent with regard to the means they adopted to gain their point…,” Fr. Engelhardt writes. “Notwithstanding the priest’s devotion to duty, his discomfited enemies would not rest. Some most prominent ruling spirits of the place importuned Bishop Mora to remove Father Mut; but a counter-petition from the church-going people of San Juan Capistrano and vicinity justly received more consideration, and so the much harassed priest remained.”

According to Olivares, some men spread lies about Fr. Mut. “He had a housekeeper,” he recalled. “The rich ones began to say the Padre was living with her and when she passed would say ‘There goes the Padre’s woman.’ When she heard of it she left for Pajaro to become a nun, but died a short time afterwards.” Other old time residents recalled that Fr. Mut actually began to fear for his life, did not want to sleep alone at the mission, and sometimes carried a gun. Ramon Yorba (1859-1947) said that one night, “a knock came to the door and a voice said ‘Padre, there is one at the point of death who needs you.’ Father Mut opened the door and a man slashed at him with a long knife – a kind of dagger – and cut the side of his neck from the ear to the front, about 5 inches, but only through the skin…. Father Mut became so nervous toward the end [of his years in Capistrano] that his mouth and jaws trembled all the time.”

Despite the rejection of the Strobel survey, Pablo Pryor didn’t give up. A second map, drawn in 1872, again laid claim to much of the community. Fortunately, it was also rejected by the government. Two more surveys of the rancho were made in 1873 and 1875, but the matter remained unsettled.

It was during this period of uncertainty that Henry Charles acquired 160 acres worth of “Valentine Script.” Thomas Valentine had owned a rancho in Northern California, lost it, but finally secured 13,000 acres worth of land script in return, which gave him the right to claim an equal amount of government land anywhere in the United States. Henry Charles now used his share to claim San Juan Capistrano, forcing a lawsuit “to determine the status of the various titles to land in the Capistrano Valley.” There were a host of claimants, all anxious to have their holdings confirmed.

Out of this lawsuit came an unusual idea. Federal law allowed existing communities to claim the land where they sat. If the community was unincorporated, the land would be granted to a judge, who in turn would deed the lots to their occupants and owners. It was a law that had never been used in Southern California, but it fit San Juan Capistrano perfectly.

In 1874, Los Angeles County Judge H.K.S. O’Melveny began the process of securing a grant to 640 acres. He appointed three commissioners to supervise a survey of the townsite – Jonathan Bacon, Frank Riverin, and of course, Father Joseph Mut. The survey was finalized in December 1875, and in 1876 Judge O’Melveny began issuing deeds to the residents of what was now an officially recognized town.

At the same time (January 1875) a final survey was made of the Rancho Boca de la Playa, placing it where it had always been – south of town. Still, it took more than four years for the government bureaucracy to complete the review process. The map was finally approved in March 1879 and a patent (deed) issued confirming the 6,607-acre grant.

But Pablo Pryor did not live to see it. In August 1878 he died under strange circumstances after drinking out of a glass previously used to pour squirrel poison. “He was esteemed and respected by all who knew him,” the Santa Ana Times reported, and “…was followed to the grave by one of the largest processions San Juan has ever known. As the grave was being closed many a one turned away, regretting the fall of one of our most amiable and enterprising citizens, deeply sympathizing with the bereaved family.”

But it is clear not everyone in town felt that way.

As for Father Mut, Fr. Engelhardt wrote that “he finally tired of the relentless opposition of the mighty ones, and was accordingly transferred to Mission San Miguel.” There he found a similar – if not so dramatic – situation. The property directly in front of the church had been included when the U.S. government deeded the mission back to the Catholic Church, “and to this day the church cannot lay claim to an approach to its front entrance.” “Upon this subject Father Mut waxes both eloquent and indignant … and it is the dream of Father Mut’s life to again have the Church property rounded out, by so much as by all duties of justice belongs to it.” (San Francisco Chronicle, 7-31-1887) With the help of the land’s new, Catholic owner, he hoped to succeed.

Father Mut continued to serve his parishioners in and around the old mission for the rest of his life. He died in 1889 at just 54 years of age. His tombstone carries the same inscription in both English and Spanish:

Erected by the San Miguel Relief Society

To the memory of Rev. Joseph Mut

Native of Dos Rius, Province of Barcelona, Spain

Died in San Miguel

Oct 3, 1889. Aged 54 years.

Suffer the little children,

and forbid them not to come to me

for the kingdom of heaven is for such.

May his soul rest in peace. Amen.

Fr. Mut’s tombstone in the cemetery at Mission San Miguel.